Is this a new era for high-speed rail in America?

If Brightline West can complete its Las Vegas to SoCal line by the 2028 Olympics, the high-speed-rail industry might be on the fast track.

Last week marked such a monumental milestone for high-speed rail in America that the railfan-in-chief can be forgiven for a bit of hyperbole.

“At long last, we’re building the first high-speed rail project in our nation’s history,” President Joe Biden said at an event in Las Vegas on Friday, announcing an unprecedented $6 billion investment in high-speed rail. “Together, we’re finally going to make high-speed rail happen between Las Vegas and Los Angeles.”

America's Unsung Rail Renaissance

You can hear them as they plug in their devices at their seat. You can hear them as they pass through the hissing automatic doors between cars. You can hear them as they enter the spacious, sparkling restrooms. “Wow.” “Nice.” “I…

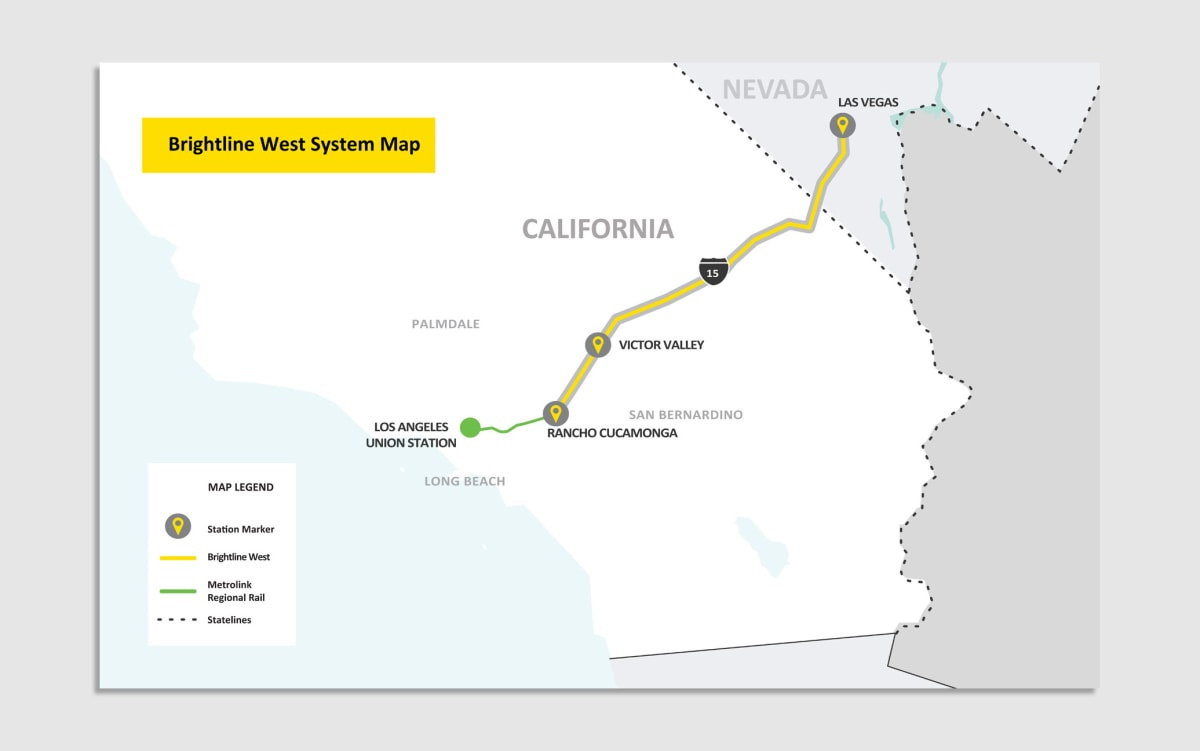

No matter that the 150 mile per hour Acela service on the Northeast Corridor technically breaks the internationally recognized velocity threshold for high-speed rail over a short stretch of its run. Or that California High-Speed Rail is already under construction in the San Joaquin Valley. Or that the new service Biden referred to, Brightline West, won’t even make it into Los Angeles County, but instead terminates in the suburb of Rancho Cucamonga.

Details, details.

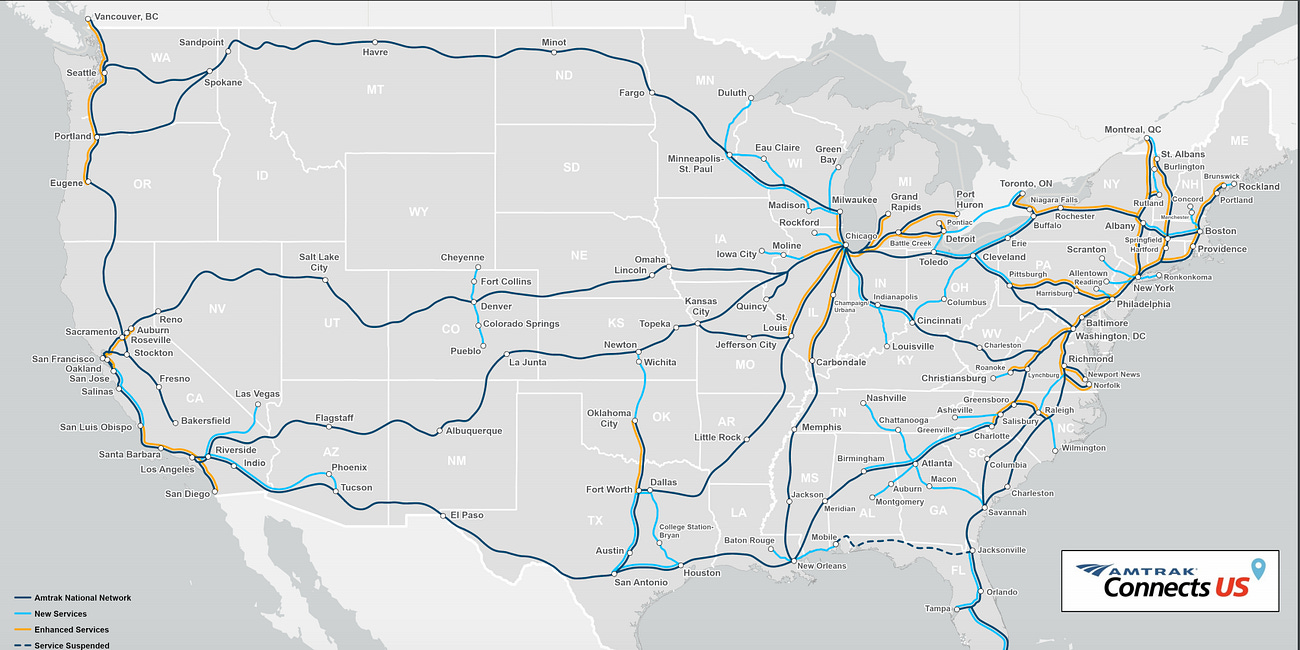

The big picture is that America has never been more bullish on high-speed rail. Thanks to the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, the government has big bucks to dole out to signature projects. And, at least for now, the nation has a president eager to get those projects underway.

The $6 billion in high-speed rail funding announced Friday will be split roughly evenly between California High-Speed Rail and Brightline West. It’s a watershed moment for both projects, but Biden’s remarks, and most media attention, have been focused on the Brightline project, which will open sooner, and serve a much bigger, more high-profile travel market.

That is, if all goes according to plan.

The $12 billion Las Vegas to Southern California project, from the same company that runs Brightline Florida, will be mostly privately funded by investors who will eventually expect a return on their investment. And those funders might not be as forgiving about cost overruns as government agencies.

As a true high-speed rail project running at speeds of up to 200 miles per hour, Brightline West will be trickier to construct than the company’s diesel-powered “higher-speed” Orlando-to-Miami line, which tops out at 125 miles per hour. Reaching those speeds, and making the trip from Las Vegas to Southern California in about 2 hours and 10 minutes, will require straighter, stronger track and an electric power source.

What’s more, Brightline’s $3 billion grant award was less than the $3.75 billion the company requested. A company spokesperson did not respond to specific questions about whether the smaller-than-hoped-for grant would affect the project’s viability, or when specifically the project anticipates breaking ground.

Despite the looming challenges for Brightline West, all signs point to go. Last week, fencing went up at the line’s Las Vegas station location on the southern end of the Strip, along with a post on X stating that the project is “breaking ground soon.” Brightline is aiming for completion by the 2028 Summer Olympics in LA—a goal Biden repeated during his remarks.

That construction timeline “seems wildly outrageous,” says Yonah Freemark, a fellow at the Urban Institute who researches transportation. “But if I’m wrong, that’s great.”

Rick Harnish, executive director of the High Speed Rail Alliance, has “a lot of confidence” Brightline can meet its self-imposed deadline. All of the necessary land is already acquired, Harnish said, and most of the route is “in a pretty easy environment to construct things in.”

Unlike California High Speed Rail’s route map, which was mainly developed based on political considerations, Brightline West follows a path of least resistance. Nearly all of its track will be in the median of Interstate-15, practically eliminating the eminent domain disputes, utility relocations, and grade-crossings that have plagued California High-Speed Rail. Brightline West’s Rancho Cucamonga terminus, likewise, insulates the project from a complex, expensive, and potentially litigious approach into the densely populated urban core of LA.

“The reality that Brightline has chosen not to actually go into Los Angeles is reflective of the difficulty the California High-Speed Rail project has faced,” Freemark said. “We continue to have a number of major barriers to getting effective projects done. There remain extremely high costs for construction throughout the United States.”

Whether this tradeoff—a more simple, less-than-ideal route—pays off for Brightline West remains to be seen.

The Magic of Electrified Trains

A remarkable technology is about to make transportation in Silicon Valley much faster, much more convenient, and much more environmentally friendly. I’m speaking, of course, about electrified trains. Unlike electric cars, autonomous cars or highway expansions

Ray Delahanty, an urban planner-turned-Youtuber, analyzed the travel market between these two metro areas using several Southern California Cheesecake Factory restaurants as starting places. He found that flying will typically be faster than Brightline West, when accounting for the schlep to Rancho Cucamonga. However, the train will almost always be faster than driving. The only places where the train will be the quickest option of all will be in the Inland Empire, close to the station, or in downtown LA, which will be connected to Brightline West with a transfer, by an hour-long trip on the Metrolink regional rail service.

Those projections bode well for Brightline West, Delahanty says, given the fact that about 85% of the roughly 50 million annual trips between the two regions happen by car. “There’s a sense that the [Las Vegas] airport is kind of hitting a capacity threshold,” says Delahanty, who lived in the Las Vegas area last year.

Overwhelming travel demand is not a major issue on California High-Speed Rail’s 171-mile initial operating segment, which will connect Bakersfield, Fresno, and Merced in the San Joaquin Valley. That project, expected to open between 2030 and 2033, is still roughly $4.7 billion short of what it needs to get to completion, even with its latest grant, a spokesperson explained. That gap will likely need to be filled by additional federal grants in the coming years. Tens of billions more will be needed to complete the project’s voter-approved route, connecting Los Angeles and San Francisco in under three hours.

Even as it steals California High-Speed Rail’s thunder, Brightline West could be a blessing in disguise for its beleaguered sibling. Preliminary studies indicate massive ridership and revenue boosts if the two systems are linked by a proposed rail line known as the High-Desert Corridor. A state-of-the-art high-speed rail service, connecting the nation’s tourism and media capitals, could also do a lot for the high-speed rail industry’s political fortunes.

“The hope within the industry is once you see that first sleek train depart Las Vegas, it’s going to seem a lot more real,” said Sean Jeans-Gail, vice president of government affairs and policy at the Rail Passengers Association. “A lot of people who assumed the California project would never arrive will go, ‘Oh, it is possible. We can do it here.’”

This article originally appeared in Fast Company. It is republished here with permission.

What great news! I hope Canada follows suit.

This is the most optimistic I’ve felt about U.S. rail in years. What’s striking is how Brightline West’s design philosophy seems to prioritize doability over perfection — choosing the I-15 median, avoiding eminent domain, sidestepping LA proper. It’s a pragmatic pivot that might finally break the cycle of planning paralysis that’s plagued California HSR.

That said, the Rancho Cucamonga terminus is a psychological hurdle. Without a true LA anchor, it risks being seen as a half-measure. The Metrolink connection is functional, but it doesn’t yet deliver the seamless “wow” factor that flips public perception.