The real problem with California Forever

New cities can be a good thing. But in order to succeed, they need to be connected to the rest of the world.

Update 3/5/24: In the wake of criticisms like those laid out in this post, the team behind California Forever committed to preserve space for rail rights of way and stations in their planned city. Read more about those changes, and the challenges of bringing rail to this site, here.

California Forever — a tech billionaire-funded city slated to rise in the outer reaches of the Bay Area — really, really wants to be embraced by urbanists.

The city (or company or political campaign) this week published a blog post called “The Urbanist Case for a New Community in Solano County.” From an urbanist perspective, there’s a lot of good stuff in the post and in the accompanying ballot measure text that Solano County voters will likely consider in November. It’s clear that the urban designers working on California Forever, including former SPUR director Gabe Metcalf, have been given a long leash to practice their craft.

Unfortunately, there’s a glaring hole in these plans: a complete lack of regional transit planning. This is California Forever’s fatal flaw that no amount of bike lanes, affordable housing, or carbon-neutral architecture can redeem. At the end of the day, California Forever will still be a sprawl development that will be accessible primarily by car. That’s not an urbanism innovation. It’s a blast from the past.

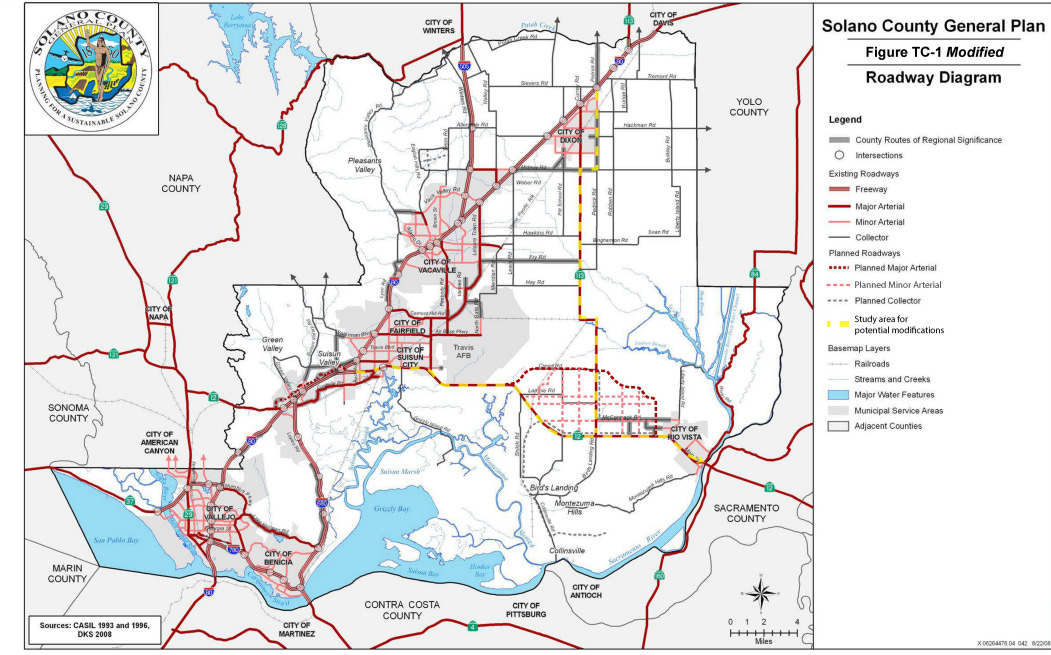

For the uninitiated, here’s a brief primer on California Forever. For the past several years, a secretive investor group called Flannery Associates has spent roughly $800 million buying up 60,000 acres of farmland between Fairfield and Rio Vista, 60 miles northeast of San Francisco. Last year, it was revealed that the group’s backers include some of the biggest names in tech, including Marc Andreesen, Michael Moritz, Laurene Powell-Jobs, and Reid Hoffman. Their ambition? Build a new city from scratch.

There has naturally been a lot of suspicion about the provenance of and motivations behind California Forever. Is it an effective altruist attempt to address the Bay Area’s housing crisis from know-better techies who are sick of San Francisco’s red tape? Is it an eminently rational business decision to build a mega-development in one of the most desirable regions in the world? Is it a shadowy scheme to create a libertarian, techno-utopian city-state?

Who knows. As the sum of media coverage has demonstrated, there’s a constellation of keywords associated with California Forever that pre-dispose people to dismiss it: billionaires, tech, sprawl, Solano County. But now that there are concrete plans in what could soon be a legally binding document, it’s worth evaluating California Forever for what it is.

This week, California Forever submitted ballot measure text to the Solano County Registrar in the hopes of qualifying for the November election. The “Solano County Homes, Jobs, and Clean Energy Initiative” is loaded with goodies, including $400 million for down-payment assistance and affordable housing, $200 million for the revitalization of the county’s existing downtowns, and tens of millions for scholarships and parks.

The ballot initiative text also reveals more about the city’s urban planning characteristics. The city will be compact, encompassing approximately 18,000 of the 60,000 acres the investor group purchased, leaving the rest for agriculture, open space and solar farms, including a wide buffer for nearby Travis Air Force Base. The total planned population will be about 400,000 people, approximately double the current population of Solano County. The city could also accommodate up to 90 million square feet of commercial and industrial space.

In order to house all of those people within a relatively small area, the city will have an average residential density of about 20 units per acre — closer to a Philadelphia rowhouse neighborhood than a California subdivision — and some mixed-use areas will see buildings rise up to eight stories high. The latest renderings show a pleasingly chaotic mix of building sizes and types, reminiscent of Seattle’s Capitol Hill neighborhood or downtown Pasadena.

Streets will be laid out in a grid inspired by the 19th century street plans for New York and San Francisco. The redundancy of the grid enables multimodal streets, with ubiquitous protected bike lanes and bus-rapid transit corridors every half mile or so. Parking will be limited, and in some areas will be in centralized “community parking facilities” that allow for more efficient use of parking spaces throughout the day.

If California Forever actually follows through on this template, the city will be well-designed in and of itself. A large share of local trips will be accomplished by walking, biking, and transit. As a self-contained entity, the city will probably have a relatively low carbon footprint.

But new cities are part of regions. Especially a new city in the exurbs of a housing-starved place like the Bay Area, whose stated purpose is to ease the region’s housing shortage. A large proportion of California Forever residents are going to be commuting to the inner Bay Area or Sacramento. Probably an even larger proportion are going to be regularly visiting the inner Bay Area and Sacramento for reasons other than work. These will be footloose Californians. There will be a lot of trips to Tahoe and Sonoma and LA and points beyond via SFO. How are they going to get there?

The Magic of Electrified Trains

A remarkable technology is about to make transportation in Silicon Valley much faster, much more convenient, and much more environmentally friendly. I’m speaking, of course, about electrified trains. Unlike electric cars, autonomous cars or highway expansions

In a car, in all likelihood. Because despite the thoughtful transportation planning for the city itself, California Forever neglects the regional transportation picture. The project’s answer to getting people in and out of the city is, essentially, to widen highways 12 and 113, thus dumping more cars onto the highway-from-hell that is I-80. There is a vague gesture in the ballot measure at transit improvements along these highways, but nothing like the bus rapid transit corridors planned for the city. There’s also a brief mention of the intent to study a possible rail connection to the Amtrak Capitol Corridor station in Fairfield and the possible reuse of an old rail corridor, but no detail.

Compared to the care and thought being put into the city itself, these regional transportation plans are pitiful. Doubly so because of the resources and influence at this group’s disposal.

They could have at the very least preserved a right of way for a future rail corridor in their masterplan to show that they’re interested in regional transit. They could have referenced existing, long-term plans to electrify the Capitol Corridor and run it at speeds of up to 150 miles per hour. (One of the concepts being studied would take advantage of the abandoned rail corridor directly adjacent to the California Forever site.) They could have discussed the Link21 project that could connect the Capitol Corridor to San Francisco and the Peninsula via a new tunnel across the Bay, or the plan to connect the Capitol Corridor to the SMART train in the North Bay. They could have made note of the BART terminus not too far away in Antioch, and considered how residents of the new city could make use of it.

If this were a truly urbanist project, these regional transportation links would have been a top priority. There would be no better way for California Forever to ingratiate itself with urbanists and environmentalists than to use its formidable power — and “A-Team” of political consultants — to call attention to the need for better transit in Solano County and across the Northern California mega-region, if not commit some funding.

As sprawl development goes, California Forever is great. Would that every new subdivision in Florida and Texas and North Carolina were aspiring to these standards. But this is the Bay Area, and these are some of the richest people in the world. They purport to be passionate about innovation and creating a model for the cities of the future. Prove it. Build the train.

My charitable suspicion is that the California Forever folks considered the extremely difficult political coordination problems they'd have to solve to get a rail connection to their new city built, taking into account the absolutely horrible state of Bay Area transit governance and paucity of real progress in the last 50 years, and decided that they already had enough expected difficulty to overcome to build the city at all and had none left to spare for regional transit. They might be wrong about that, but it seems hard to blame them for betting that way.

Leaving out public transit is a big miss. I hope they're able to connect with their region via a decent transit system.