Earlier this year, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Lawrence Wright published a feature story in the New Yorker entitled, “The Astonishing Transformation of Austin.” It was the latest and most ambitious contribution to the flourishing sub-genre of urban change journalism. Before COVID radically altered the city’s narrative, San Francisco was the main subject of these reports. Virtually every economically successful city, from New York to Seattle, has been examined in such a light by local and national outlets over the last few years. The focus of this genre is usually about how the new people moving in are changing the cultural fabric of the city, and in the process, depleting the city’s soul.

Wright’s piece actually avoids the worst pitfalls of the urban change genre, which often devolves into nostalgic, naive longing for the city the author moved to so many years ago. (A cameo from ever equanimous Matthew McConaughey, Austin’s self-appointed “minister of culture,” helps keep things in perspective.) But Wright’s piece, like many other big swings that explore the state of a major city, is deficient in another way. Over the course of 13,000 words, Wright makes no mention of Austin’s most significant urban planning debates: The city’s planned light rail system and the massive freeway expansion slated for the city’s downtown. These contentious projects could shape Austin’s future more profoundly than any other issue discussed in the piece. Urban planning, as much as anything else, will determine the state of Austin’s soul.

Despite the voguishness of urban planning, the field’s nuts and bolts continue to be neglected in the public discourse on cities. Gentrification, public safety, economic development and governance issues are much more immediate and comprehensible than long-range planning decisions. That is until those planning decisions are made permanent in steel and concrete, and not only the city’s physical form, but its way of life, are altered forever.

Austin, America’s fastest growing, most dynamic big city, is where these kinds of generational infrastructure projects could have the most transformative effect. This young city is desperate to urbanize; to make walking, biking and transit into no-brainer transportation options; to accommodate the massive inflow of newcomers without playing the tired, zero-sum game of traffic and parking.

But Austin is also a poster-child for America’s muddled, self-defeating transportation policy. At a time when freeway expansions are widely understood to be not just pointless but actively harmful, and transit has been endorsed by voters as the way of the future, Austinites are finding that logic and democracy don’t apply in the transportation space.

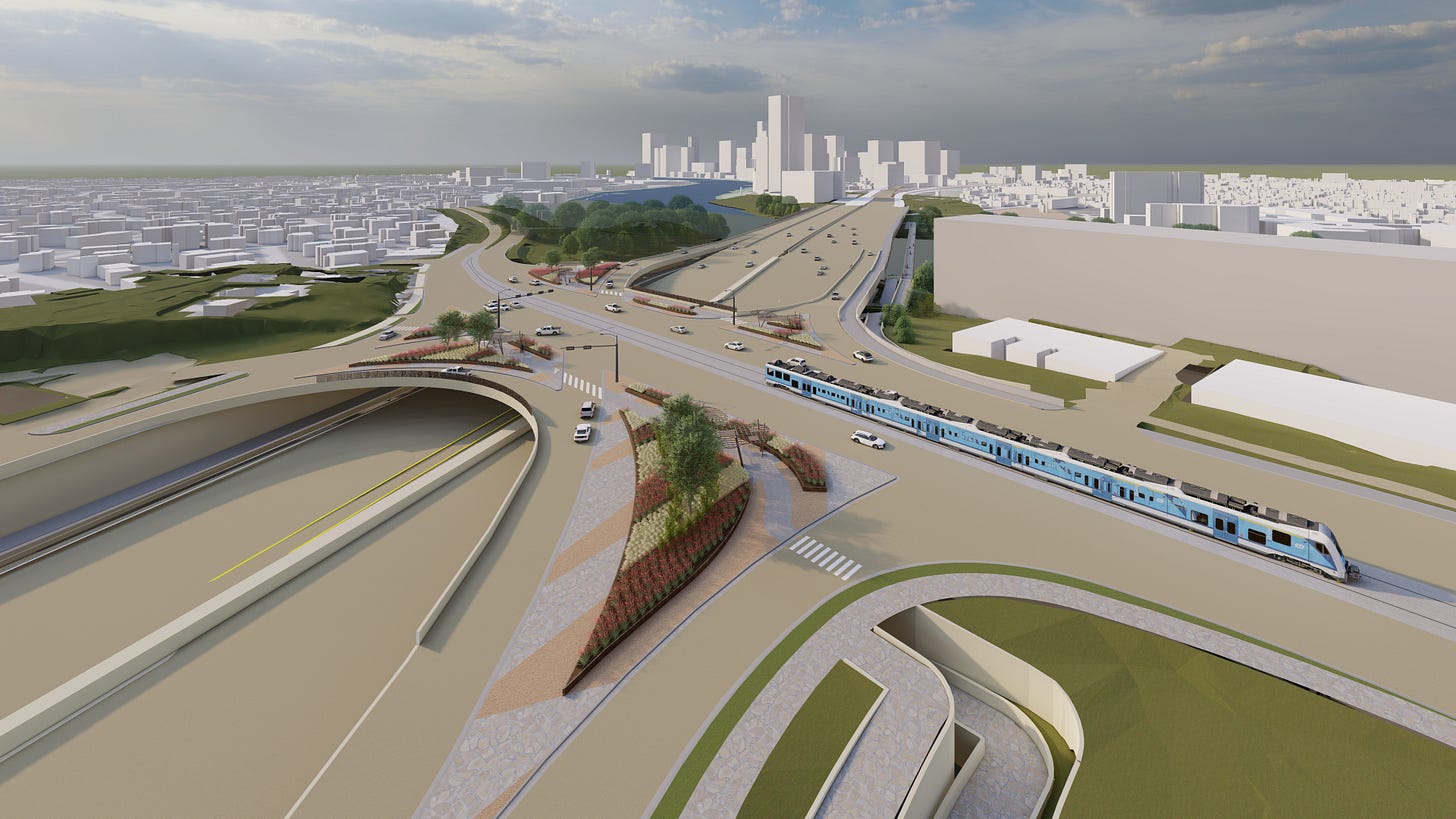

Consider the parallel paths taken by the city’s Project Connect light rail plan, and the I-35 expansion project, administered by the Texas Department of Transportation.

Building transit is like pulling teeth

In 2020, 58% of Austin voters approved a property tax increase to fund the construction of a 28 mile light rail system, including a downtown subway tunnel, a direct line to the airport, and connections to fast growing neighborhoods like South Congress. In 2022, city officials announced that the projected cost of the transit system had nearly doubled, from $5.8 billion to $10.3 billion. In response, the following year officials unveiled a considerably scaled back plan, running only 10 miles. The downtown subway tunnel was nixed, and the connection to the airport left as a future “priority extension.” The new plan will cost about $3.5 billion, but is officially budgeted at $5 billion to provide a 40% cushion for potential cost overruns.

As the light rail system was getting scaled back, Republicans in the Texas State Legislature introduced a bill that would have required another vote of the people before the city’s transit agency could issue bonds and debt for the project. The bill, supported by an opinion from subsequently impeached Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton, would have put the light rail project in serious jeopardy. The bill failed to advance, but Paxton’s opinion — and the now-acquitted Paxton — could continue to be a vulnerability for the project.

So Project Connect is limping forward, awaiting matching grants from the Federal Transit Administration that will ultimately fund about half of its construction costs. But these grants are not guaranteed, and the manner in which they’re doled out limited the ambitions of the project. Initially, Austin had planned to apply for two New Starts grants for its two planned light rail lines. But as planning progressed, it became clear that awarding a single city with two New Starts grants simultaneously was “not how the FTA does things,” a local transit insider told me. Likewise, the massive contingency cushion built into the project is there, in part, to provide assurances to the FTA.

In sum, a wide array of forces have been set against the successful development of light rail in Austin. The only thing the project has going for it is public opinion.

Highway expansions get the red carpet treatment

Compare this gauntlet to the expansion of I-35 through the heart of Austin. In discussion for years, the I-35 expansion began formal planning in 2020 when TxDOT initiated its environmental impact report and feasibility study. The 8 mile freeway widening project will take the existing road from its current 12 lanes to 20 lanes in some sections, including frontage roads. The expanded highway, already a barrier between downtown and the historically Black and Latino communities of East Austin will be 365 feet wide at some points, and will necessitate the displacement of 59 businesses and 51 homes.

The $4.9 billion project is just one of a trio of I-35 expansion projects spanning 28 miles through the Austin metro area with a total pricetag of $7.5 billion. Activist groups led by Rethink35 filed a lawsuit arguing TxDOT split the project into three parts to conceal its true environmental impact. (The advocacy groups eventually abandoned their lawsuit, and are now pursuing a new legal strategy to stop the project.)

TxDOT also made some very questionable projections for vehicle miles traveled and greenhouse gas emissions in its environmental impact report for the project. As transportation policy expert Kevin DeGood pointed out, TxDOT made the “bananas” assertion that widening the freeway would barely increase driving and emissions compared to a scenario in which the freeway was not expanded at all. (That finding contradicts decades of evidence about “induced demand”.)

But there’s no clear avenue to challenge these projections, since TxDOT has the authority to “self-certify” its environmental impact report. It did so last month, paving the way for construction to begin next year. There will be no high-stakes federal grant application process for the freeway expansion. The feds dole out highway funds to state DOTs by formula, that is to say automatically, which states may then use however they please. The bipartisan infrastructure law doubled those allocations, giving freeway-loving states like Texas a lot more money for Texas-sized freeways.

It’s smooth sailing for the I-35 expansion project, despite the opposition of numerous elected officials, from city council members, to state reps, to members of Congress. (Austin Mayor Kirk Watson supports the project.) Unlike the light rail plan, the highway project was never subjected to a vote of the people. And Texas state leaders have stayed out of the way — except to insist that highway tolling, the only effective congestion reduction tool, would not be permitted in this project.

In sum, all of the mechanics of state and federal government are aligned to promote the continual expansion of freeways in Texas, regardless of public opinion, the environment, and rational analysis.

Why transportation policy matters to a city’s soul

In the 1970s, architecture critics like Marshall Berman and Ada Louise Huxtable began using the term “urbicide” to describe what happened to neighborhoods like the South Bronx after Robert Moses plowed his freeways through. In the current era of freeway expansions, the sheer destruction is not as severe. Projects like the I-35 expansion contain greenwashed niceties, like small freeway caps in specific areas. But the freeway expansion is still a form of urbicide, foreclosing a more urban future for the city of Austin.

By pumping untold (see above) thousands of additional vehicles into the heart of the city every day, this project will choke the streets with traffic and make walking and biking even less safe. It will decrease support for bike lanes and transit-only lanes, and increase support for future roadway expansions. It will create further demand for parking in dense urban neighborhoods, increasing the cost of new housing. It will turbo-charge NIMBYism, as drivers agitate against any change that will worsen traffic and parking even further. And it will undermine the city’s light rail plans, by producing a cityscape and an urban lifestyle anathema to transit use.

Suspend your disbelief for a moment. What if Austin and TxDOT made an all-out effort to construct the full 28 mile light rail system approved by voters as quickly as possible? The money is there: States are allowed to use formula highway dollars for public transit development. Instead of massively expanding I-35, TxDOT could tear down the section that runs through central Austin, and turn it into a surface level boulevard, like the Embarcadero in San Francisco. There’d be plenty of room left for affordable housing, parks, and transit. One of the two perimeter freeways that parallel the interstate at the edges of the Austin metro area, US-183 and TX-1, could be redesignated as I-35.

This totally feasible vision, which Austin urbanists have been advocating for years, would change everything. Once the car is dethroned, Austinites would discover just how spacious their city is. Without being encapsulated in their cars, oldtimers and newcomers would be able mingle and create a new cultural fusion, even weirder than what came before.

A wonderful community of urbanists in Austin — profiled in Megan Kimble’s forthcoming book, City Limits — are working hard to achieve this vision of the future. But given TxDOT’s power, their efforts may not be enough to prevent this generational urban planning mistake in America’s most dynamic city.

Part of the problem is that the vast numbers of people who love cities and care about their future don’t necessarily understand the profound links between urban planning and the urban experience; between the infrastructure of cities and the culture of cities. What would it take to draw that connection more clearly? A 13,000-word New Yorker piece would be a good start. Some agitation from a pop-culture icon like McConaughey would be a giant leap. At the very least, a visionary mayor could take a bold stand, articulating what cities and their people lose when they mortgage their future to car dependence, and what they gain when they set themselves free.

“Is Austin going to be one of the last cities to get it wrong?” Austin urbanist Greg Anderson recently asked the Austin City Council during a hearing. “Or is it going to be one of the first cities to get it right?”