Amtrak is still riding the nostalgia train

Small towns and neglected regions deserve passenger rail service. But long-distance trains aren't the best way to do it.

Oh Amtrak, you beautiful contradiction. With one hand, you’re bringing about an American rail renaissance, investing in new high-demand routes and reinvigorating old workhorses like the Northeast Corridor. Yet with the other hand, you’re laying the groundwork for more of the nostalgic, transcontinental train services that have held passenger rail back for decades.

The progress that Amtrak and the Federal Railroad Administration have made during the Biden Administration is well-publicized, especially in this newsletter. But now America’s passenger rail bureaucracy is showing another side of itself.

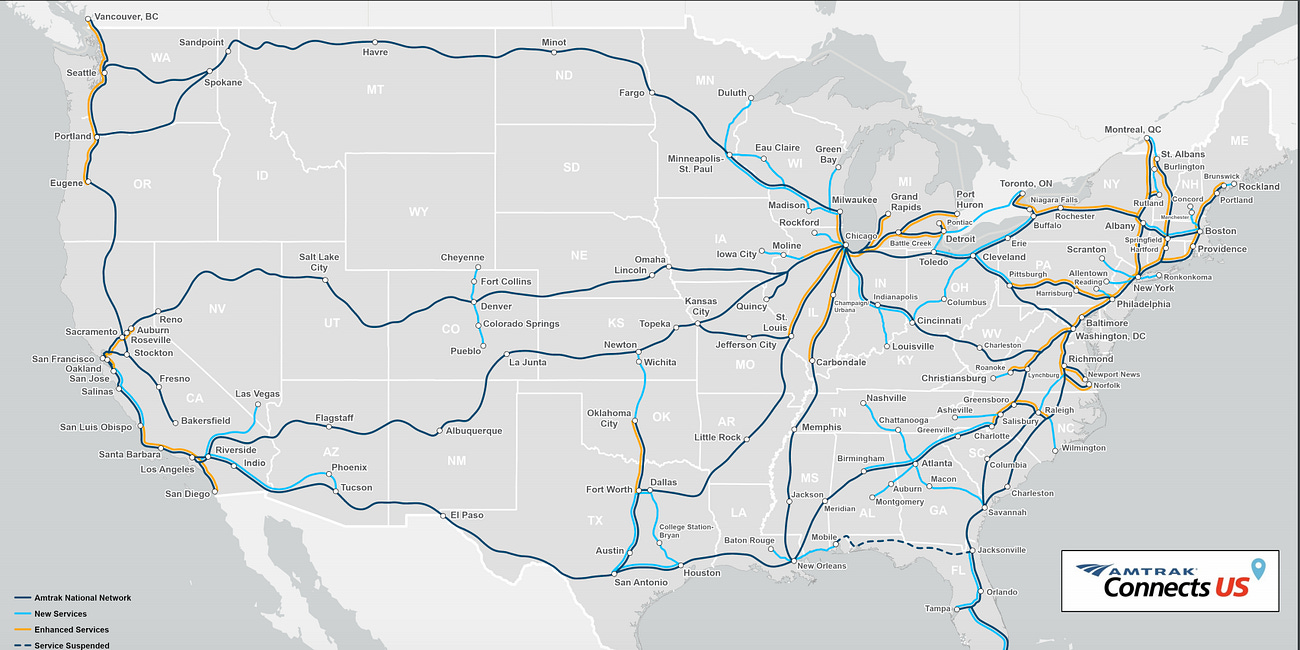

Last week, the FRA released a Long-Distance Service Study envisioning 15 new routes of between 750 and 2,000 miles criss-crossing the continent. If implemented, this plan would more than double the long-distance routes and track mileage that Amtrak currently operates.

It sure is a pretty map. More rail service to more diverse places is much-needed. But more of this kind of rail service, based on 19th century travel patterns, is throwing good money after bad.

Fortunately, none of these plans are official. Federal administrators are only just beginning to think through how these plans could become reality. There’s still time for planners to chop these lines up into more manageable, more useful segments.

Amtrak and the FRA are starting in an awfully vintage place, however. One of the premises behind the study was to reevaluate long-distance services that were cancelled when Amtrak was created in 1971, which gives a sense of which direction we’re traveling through history.

Is this a new era for high-speed rail in America?

Last week marked such a monumental milestone for high-speed rail in America that the railfan-in-chief can be forgiven for a bit of hyperbole. “At long last, we’re building the first high-speed rail project in our nation’s history,” President Joe Biden

Let’s start with the good parts of the plan. The expanded long-distance network would provide rail service to an additional 45 million Americans, including huge increases in the rural and tribal populations with access to trains. Twenty four additional Congressional districts, as well as the large majority of universities, medical centers, and National Parks across the country would have access to rail.

All of these places ought to have rail service, especially as Greyhound and other bus companies pull back. But connecting them via routes stretching from New York to Houston, or Minneapolis to Phoenix, is a bad idea.

There are several basic, practical issues with long-distance trains. A lot can go wrong when you’re covering so many miles, making trip durations unreliable and delays common. When journeys last between 24 and 36 hours, many stops will be served at extremely inconvenient times of day. For example, if you want to take Amtrak from Cleveland to Chicago, your only two options are at 3:00 am or 4:00 am on long-distance trains that originate in New York and Washington. These trains also require expensive sleeping and dining accommodations, increasing costs at every phase of construction and operation. Most importantly, long-distance trains just aren’t that popular, because they’re typically not time- or cost-competitive with other modes of transportation.

Though some people hop on long-distance trains for shorter trips, those going from end-to-end are often tourists. These historic rail services — still plying the same routes with the same names as they did a century ago, in many cases — are a wonderful way to see America’s natural beauty. They may as well be considered rolling national parks, since long-distance trains, unlike far more popular state-supported lines, are completely federally funded.

From the get-go, long-distance trains have been a major drag on Amtrak’s finances. As recently as 2019, Amtrak leaders were looking to trim some of these services. But as in past decades, these routes have proven too politically popular to discard. Senators and Members of Congress from sparsely populated areas want to keep their train, and understandably so. Long-distance routes are also cherished by state and national rail passenger associations. When the stars aligned to give Amtrak a boost with the 2021 Infrastructure Bill, legislators took the familiar both/and track, providing funding opportunities to long-distance, state-supported, and new high-speed lines.

But even with a much-improved financial situation, Amtrak should be judicious with its spending. Before this long-distance planning exercise goes any further, it’s worth reckoning with the costs of these kinds of services.

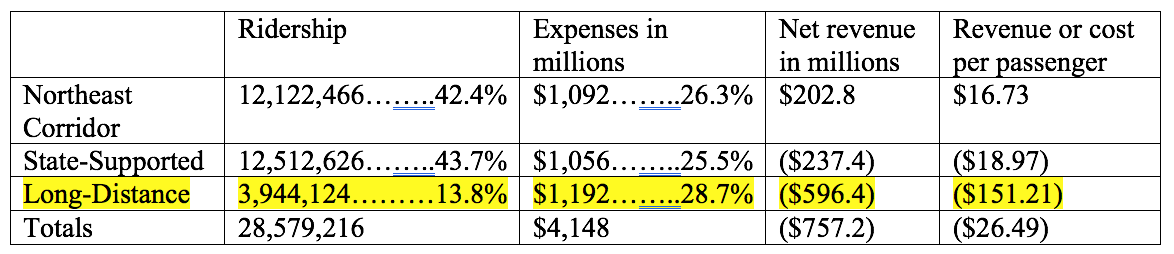

In Fiscal Year 2023, long-distance trains carried about 4 million riders, or roughly 14% of all Amtrak passengers. However, those lines accounted for about 28% of Amtrak’s expenses, necessitating deep subsidies. The agency lost nearly $600 million on long-distance services last year, or about $150 per passenger. That’s an orders of magnitude difference compared to Amtrak’s state-supported routes, or the profitable Northeast Corridor.

These existing long-distance routes aren’t going anywhere anytime soon. The Infrastructure bill enshrined their continued operation in law for the foreseeable future. Still, it’s worth asking, is this a model we should double down on?

To equitably spread rail service across the country, some long-distance routes will always be necessary, especially across the vast American west. But in many cases, it makes more sense to operate shorter routes, more frequently, anchored by big-city pairs with a significant inter-city travel market. Rich Sampson, AKA @RAILMag, started doing this exercise on X: Instead of a route going all the way from Chicago to Miami, for instance, how about breaking it up in Nashville?

A couple of years ago, Sampson crayoned a conceptual map showing what a comprehensive, ridership-focused national rail network might look like. It would preserve the existing long-distance network, while largely adding new routes of 500 miles or less, like Cleveland to Cincinnati, or Charlotte to Atlanta. These shorter, higher-demand routes would still hit a lot of rural destinations in between the principal city pairs. And they could potentially serve those destinations at much higher frequencies, and at much more appealing times of day.

To Amtrak and the FRA’s credit, there’s also a lot of planning work going on related to these more optimal routes. Sampson’s map represents a middle ground between the FRA’s Long-Distance Service Study and Amtrak’s Connect US plan for increasing state-supported routes (the light blue lines on the map below). In an ideal world, there need not be such a stark division between these two service types. All would be seen as an appealing travel option, going places people want to go, with multiple departures at convenient times of day.

America's Unsung Rail Renaissance

You can hear them as they plug in their devices at their seat. You can hear them as they pass through the hissing automatic doors between cars. You can hear them as they enter the spacious, sparkling restrooms. “Wow.” “Nice.” “I…

Realistically, however, some expansion of long-distance service could be politically expedient. Investing in a handful of strategically located long-distance routes could help generate momentum for rail in states that are resistant to funding it themselves. Two of the likeliest long-distance routes to move forward are Atlanta to Dallas and a new Chicago to Seattle connection. Legislators in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Montana are eager for more train service. Their neighboring states, not so much. Long-distance routes smooth over these inter-state conflicts by essentially throwing federal money at them.

Another model could be to establish short lines on the busier sections of long-distance routes. A planned service connecting Chicago and Minneapolis will do just that, enhancing a brief stretch of the much longer Empire Builder out to Seattle.

But these special deals do not a robust national rail program make. There’s so much exciting progress happening in America’s passenger rail system. It would be a shame if it didn’t result in more fundamental shifts. High-speed rail, electrification, improving relations with the freight railroads, and reimagining long-distance service are among the higher-order changes that could really transform passenger rail in America.

What this article is proposing is an even more vintage look at the American passenger train. And that's OK.

What the article is suggesting is a return to the long lost local. These were slowly bumped off long before Amtrak took over leaving only the first class limiteds. The local day train fell victim to improved highways. But our highways are crowded. So we need these little local short runs once more.

Terrific article, Ben! I hope the powers that be read it and learn. Thank you.