In Defense of Inclusionary Zoning

The policy needs to be used judiciously. But in the right contexts, inclusionary zoning can absolutely coexist with robust housing production.

Inclusionary zoning is a tax on new construction. So reads the headline of a recent piece by Matt Yglesias in Slow Boring. It’s technically an accurate statement. But those words, Yglesias’ article, and the broader discourse on inclusionary zoning miss a lot of nuance.

It’s especially important to get a fuller picture of inclusionary zoning now, with the policy potentially coming into the crosshairs of the U.S. Supreme Court. Housing advocates who would celebrate the elimination of this value capture tool should be careful what they wish for.

The basic concept of inclusionary zoning is this: When a developer wants to construct a housing project, they are required to dedicate a certain percentage of their units as below-market-rate affordable housing or pay a commensurate fee. (I wrote a CityLab University explainer on the topic a few years ago.)

A poorly designed inclusionary zoning policy can certainly reduce overall housing production and worsen affordability in a city over the long term, as Yglesias and likeminded critics emphasize. But, in the right contexts, inclusionary zoning can absolutely coexist with robust housing production. The specific parameters of the policy, the state of the local housing market, and the type (high-density vs. low-density) and location (desirable or not) of the development in question matter a great deal for the success of a given inclusionary zoning policy.

Inclusionary zoning can provide additional benefits in terms of economic and social integration. It can also help build political support for housing construction, allowing residents to feel as if new development is for them, not just wealthy newcomers. But that can only happen if new projects are actually built. For inclusionary zoning to succeed, it needs to be carefully calibrated in order to ensure development remains economically viable.

Part of the challenge with the inclusionary zoning debate is the term itself. Inclusionary zoning is not the antithesis of exclusionary zoning. It’s a completely different phenomenon. Exclusionary zoning is basically a synonym for single-family zoning; the requirement that the only type of home allowed in a given neighborhood is one that is expensive by design.

Adopting inclusionary zoning will not fix the exclusionary zoning in your city. In fact, inclusionary zoning can make exclusionary zoning even worse, by making development more difficult in the limited number of places where it is allowed at all.

In far too many cases, inclusionary zoning can represent a bad faith attempt to ban or significantly limit new housing construction. The most egregious examples of these kinds of policies are in small, liberal suburbs in California and the Northeast.

In East Palo Alto, for instance, inclusionary zoning regulations require that projects with two structures, like a new home with a backyard cottage, designate one of those units as below-market-rate. As an alternative, the builder can pay a fee of $55,000. This is effectively a 50 percent inclusionary zoning requirement. It’s a bad policy that makes it economically impossible to build new housing.

A small-time builder subject to East Palo Alto’s rule has mounted a lawsuit based on a 2015 Supreme Court ruling that describes some fees associated with new housing development as unconstitutional “takings” of private property. This could be another test case designed to see if the Court will go even further in rolling back or eliminating inclusionary zoning.

But not all inclusionary zoning ordinances are as self-defeating as East Palo Alto’s.

Inclusionary zoning can be, and has been, a successful policy. It tends to work best in places with high-density zoning; when it’s paired with incentives like tax abatements, density bonuses, or low-interest financing; and when it can change in response to shifting economic conditions.

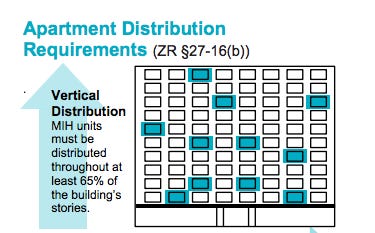

Consider New York City’s Mandatory Inclusionary Housing program, established in 2016, which requires developers to designate between 20 and 30 percent of new homes in a project as below market rate housing. As with other inclusionary zoning programs, developers can choose to dedicate more units for middle income residents, or fewer units for lower income residents. Until last year, New York developers were also able to use MIH in concert with the 421a tax abatement program, reducing their property tax bills in exchange for providing affordable housing.

Despite its name, the program is not mandatory for every project citywide. It only applies in certain recently rezoned areas and for projects seeking zoning variances. One of the first neighborhood rezonings subject to MIH was Gowanus in Brooklyn. Since the rezoning went into effect in 2021, development has proceeded remarkably fast. In just two years, 52 projects containing over 7,000 units were approved in the development area. Today, the neighborhood is one of the most radically transformed corners of New York, with dozens of new residential buildings, some rising over thirty stories, surrounding the Gowanus Canal.

All of those buildings are subject to MIH. It may be a tax on new construction, but it’s one that developers are willing to pay to build big projects in an exceedingly desirable part of Brooklyn. (Gowanus proper, bisected by its stinky canal, has not traditionally been a real estate hot spot, but it is surrounded by some of the borough’s most expensive neighborhoods.) As a result, one out of every four units in those glassy towers will house someone who otherwise would not be able to afford to live in the neighborhood.

A similar effect could be seen in SoMa during San Francisco’s pre-COVID building boomlet. Between 2005 and 2021, the neighborhood saw the construction of about 12,000 homes. Roughly 9,000 were market rate and 3,000 were affordable, with about 1,000 of those affordable homes being financed by way of the city’s inclusionary zoning ordinance. Racial diversity increased alongside the new development, with the neighborhood’s Black, Asian, and Hispanic populations rising at a faster rate than the white population.1

When development ground to a halt following the pandemic, San Francisco leaders recognized that their inclusionary zoning requirements were an impediment to new construction. So, in 2023, they reduced the percentage of affordable units required dramatically, from about 22 percent to 12 percent. Development remains anemic in the city. But many projects have since re-submitted their applications under the new, lower inclusionary zoning rates. With San Francisco rents rising rapidly, more developers will probably want to press go soon.

It’s important to acknowledge that the building booms in both Gowanus and SoMa are at least partially products of ultra-restrictive zoning elsewhere in the city and metro area. These neighborhoods are among the few “release valves” for new housing to go. In a market where housing is scarce and expensive, developers will be more willing to pay the inclusionary zoning tax.

But even under a broadly permissive zoning regime, there are still going to be places and building types that are higher value, and are therefore better equipped to coexist with inclusionary zoning. The high-rises and full-block five-over-ones in SoMa and Gowanus lend themselves better to inclusionary zoning than “missing middle” sixplexes and townhouse clusters, since the marginal cost of adding inclusionary units is typically more manageable in larger projects. These particular neighborhoods have a lot of underutilized parking lots and industrial sites where redevelopment costs are lower, which means projects can support higher inclusionary rates. Centrally located, expensive neighborhoods are also generally more appropriate for inclusionary zoning.

Targeting inclusionary zoning to these kinds of places could help address many of the policy’s side-effects. Broad-based, citywide inclusionary zoning policies like Los Angeles’ Transit Oriented Communities program, the subject of a major study showing that the policy decreases housing production and increases housing costs, are probably less effective than more geographically focused programs.

However, there are examples of inclusionary zoning working across large geographies, and even in lower-density areas. The Mt. Laurel doctrine in New Jersey functions much like a statewide inclusionary zoning ordinance that applies specifically to the most exclusionary suburbs.

Crucially, Mt. Laurel doesn’t simply impose an affordability percentage on new development and leave things at that. It requires municipalities to adopt zoning that will ensure a certain number of affordable and market rate homes will actually get built. And it imposes builders remedies — allowing developers to bypass zoning — on municipalities that fail to comply. The goal is building mixed-income housing. The policy recognizes that there are many ways to achieve that end.

The law has been very effective since it was strengthened in 2015, generating 69,000 homes through 2022, about 31 percent of which are below-market-rate. It’s a major reason New Jersey is the most pro-housing, most affordable state in the urban Northeast.

Montgomery County, Maryland also has a successful inclusionary zoning program, which it it bills as the nation’s first. Since its establishment in 1976, the program has produced over 17,000 affordable homes in this D.C. suburb. Here, inclusionary zoning is tied to a system of density bonuses that allow developers to build more units than zoning would otherwise allow in exchange for providing affordable units. The requirement also kicks in for developments larger than 20 units, which seems more reasonable than the 10-unit threshold that’s common in other cities.

Given this legacy, it was a logical next step for Montgomery County to move into mixed-income public development, also known as social housing. This concept is based on very similar value capture principles. In social housing, rents from market-rate units directly subsidize those of below-market rate units in the same building, just as with inclusionary zoning. Except, in the case of social housing, the affordable units aren’t a tax, they’re a feature.

Montgomery County’s social housing fund has partnered with private developers to include significant numbers of affordable homes in their projects. This is, in effect, a model of funded inclusionary zoning, where ambitious affordability targets are reached with the help of public subsidies. Though no longer “free” to the public, as traditional inclusionary zoning appears to be, funded inclusionary zoning can provide good value by getting affordable units built at a lower cost than a ground-up, 100 percent affordable development.

These principles are an important component of European social housing developments, like Clichy-Batignolles in Paris. There, public and private funds were combined to produce a gorgeous 3,400 unit development with 50 percent mixed-income social housing, 20 percent rent control apartments, and 30 percent market rate condos.

In fact, inclusionary zoning is ubiquitous throughout Europe and elsewhere in the world. It is not the only reason that other countries are better at producing affordable and abundant housing. There are many other policy levers to pull. But it would be a mistake for the U.S. to deprive itself of this tool. As with so many other dimensions of urbanism — if other countries have figured it out, then we can too.

I came across this data on SoMa’s development as part of the environmental impact report on 469 Stevenson Street, a 495-unit tower with 78 inclusionary affordable units slated to be built on a parking lot. The report came in response to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors blocking the project a year prior under California’s environmental law, after advocates claimed that it would accelerate gentrification. The report found those concerns to be without merit.

The project died in planning purgatory, but it lives on as a symbol of San Francisco NIMBYism run amok. The absurdity of the 469 Stevenson saga contributed to a realignment of city politics in a more pro-housing direction. It was also invoked in the successful legislative push to exempt urban housing developments from the California Environmental Quality Act.

Good, nuanced piece. No one thinks IZ is a panacea, but neither is laissez faire upzoning. Both are necessary. As Vatz says, the devil of any housing policy is in the details. So his blanket denunciation that ignores the fact there are more than a thousand IZ laws, all varied based on local market conditions and political feasibility, rings ideological. IZ is not a net cost, much less a “tax” when it is funded with tax credits/abatements, valuable density bonuses and/or other offsets. (If critics want to go after a true tax they should focus on impact fees. Or Adequate Public Facilities ordinances that literally bar development.) The equation should also consider that the marginal cost of an IZ unit is less than the per unit cost of building traditional 100% subsidized housing—which faces far steeper NIMBY barriers than a site secured by private developers for a project that is 80-90% market rate apartments. But most importantly, the social value gained by producing integrated housing in a neighborhood where growth is occurring, and that likely resisted affordable housing for decades, outweighs the value of maximizing sheer numbers and should not be so glibly dismissed. Lets not forget that the mid-century era of maximum housing production built the segregated white suburbs and huge concentrations of segregated public and subsidized housing in cities that plague us today. To make measurable progress toward residential (and school) integration we at least have to stop replicating and reinforcing segregation.

spot on piece. an important angle to consider in the IZ context is school integration. IZ helps get more low-income families into good school zones, which decreases segregation and also has important effects on social mobility. i don't think vouchers / charter schools can do this quite in the same way, though of course they do help (and programs like MTO are great too). just another factor to throw in the mix when thinking about whether an IZ "tax" is appropriately calibrated