San Francisco grows up and slims down

Developers are responding to more generous zoning rules with a bevy of skinny apartment buildings. That's a good thing.

San Francisco is gradually, fitfully disentangling itself from the anti-housing red tape that has strangled the city for years. Evidence of these changes is not particularly visible just yet. The city’s economic doom-loop, a high interest rate environment, and some remaining anti-housing policies have prevented most projects from breaking ground.

But green shoots are starting to pop up in Planning Department submissions. These project proposals present the outlines of a new residential typology for San Francisco. Developers are responding to more generous zoning regulations by growing tall and slim. They are taking standard, 25-foot wide lots, and proposing buildings of seven or more stories. One project, 777 Sutter in Lower Nob Hill, is going up to 240 feet on a 35-foot wide lot. (I provide a rundown of these projects below.)

In the next year, San Francisco will finalize its state-mandated rezoning process that will allow more housing construction across the city’s residential neighborhoods, where building heights have long been capped at 40 feet. This new crop of projects might help cool down an overheated public discourse around the rezoning.

These skinny apartment buildings demonstrate that new development in San Francisco will look nothing like the ominous blocky renderings published by the group Neighborhoods United SF. They should also serve as a rebuttal to critics who disingenuously claim that the rezoning will be a repeat of the urban renewal era that leveled much of the Fillmore District.

Cobbling together multiple lots is expensive and time-consuming. Most city and state upzoning policies either outright prohibit or make it very expensive to redevelop properties currently occupied by tenants. That means developers are incentivized to build up, on a single lot, rather than out, onto multiple lots.

The projects highlighted here are, for the most part, replacing marginal non-residential buildings. One will go up atop a one-story restaurant. Another will rise over an accessory garage.

From an urban design perspective, all of this is to the good. Skinny buildings are far more visually interesting than wide ones. They allow for gradual, lot-by-lot neighborhood change, rather than the “cataclysmic” block-by-block redevelopment that Jane Jacobs railed against. They enable neighborhoods to grow while still retaining a large number of historic buildings. They create the potential for small ground floor storefronts, appropriate for a cafe or convenience store, rather than a CVS or a bank branch.

These skinny buildings would not be unusual in New York, but for San Francisco, they mark a significant architectural shift, or at least a long historical reversion. In fact, a handful of San Francisco’s finest old apartment buildings are similarly proportioned. See: 2238 Hyde and its neighbors atop Russian Hill, or 2500 Steiner facing Alta Plaza Park.

Narrow apartment buildings will become even more economically viable if the city legalizes single-stair buildings, which it appears poised to do. One stairwell in an apartment building, as opposed to the two currently required, leaves more rentable space, lowering costs for developers and future tenants. This building code change would also allow much greater architectural flexibility for small lot structures going forward.1

As with all things San Francisco development, the usual caveats apply: All of the cemeteries of Colma couldn’t fit the the architectural plans of the city’s dead projects. There’s no guarantee that the current crop of proposals will actually be built.

But there’s reason to believe these projects could fare better than their ancestors. That’s largely because of SB 423, a state law that went into effect this year. Because of this law, all zoning-compliant housing developments — including those taking advantage of bonuses that effectively double the density of existing zoning — are on the fast track. The law guarantees project approvals within 90 days for smaller projects, and 180 days for larger ones. No longer do projects need discretionary approval from the Planning Commission. If Planning Department staff determine that it meets zoning requirements, it gets approved.

***************************************************************

Without further ado, here’s the skinny on some of San Francisco’s most intriguing new projects. (Shoutout to SF YIMBY for tracking these projects, and collecting images and data from their public filings.)

777 Sutter is the most dramatic and controversial of the bunch. This 35-foot wide, 240-foot tall tower in Lower Nob Hill would include just 36 units. Several of them would be four or five-bedrooms. More family-sized homes has long been a rallying cry of those opposed to development in this neighborhood, but some neighbors still don’t like this project. However, with SB 423 in effect, neighbors no longer have the ability to kill this proposal at the Planning Commission or Board of Supervisors.

5172 Mission, across town in the Excelsior, would rise 70 feet and include 9 units. This project is the most architecturally interesting of the bunch, with deeply recessed windows and loft-style double-height apartments.

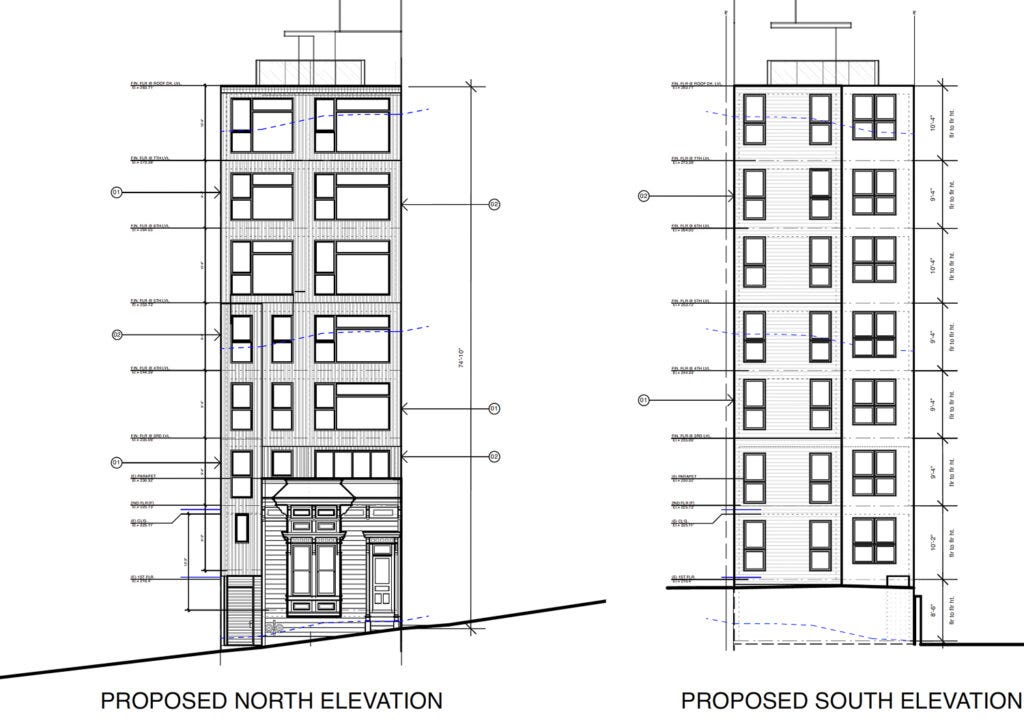

2083 Ellis in NoPa would rise 74 feet and include 9 units. The most interesting feature of this project is the preservation of the lot’s current occupant, a small Italianate Victorian cottage. More of this kind of facade preservation would help San Franciscans warm to new development.

1736 Filbert, a 10-unit 78-foot tall project in Cow Hollow, is sure to cause controversy. This is the city’s affluent NIMBY heartland, where tall buildings were banished decades ago to preserve million dollar views. This garage-replacing project will retain three apartments in the backyard.

991 Howard in SoMa will rise 80 feet, encompassing four full-floor apartments and two stories of commercial and office space. In a neighborhood accustomed to large-scale development, this project likely won’t be controversial. But the rendering shows how skinny new buildings can add texture to a San Francisco streetscape.

See these single-stair explainers by Alfred Twu and Michael Eliason.

I'm excited to hear we're getting buildings with smaller footprints even without the single stair law. I always liked the diversity of buildings north of Market compared to the block-sized towers in SOMA and I think the lot size is why.

I wonder what Jane Jacobs would have thought. She’s a proponent of high density on small lots, the argument being that since each building or development decays at a roughly uniform rate, having lots of separately developed lots developed at different timescales on an urban block means that the block is constantly regenerating rather than undergoing cycles of deterioration and urban renewal all together.