The future of transit in LA, explained

LA is America's 21st century transit laboratory. Here's the good, the bad, and the weird.

The 2013 movie, Her, depicts a dystopia where AI virtual assistants supplant the need for authentic human connection. But, one has to admit, this futuristic vision of Los Angeles has great transit. It’s hard not to envy Joaquin Phoenix, as Theodore Twombly, dancing through a busy subway station and criss-crossing the city on elevated trains.

A decade after the film came out, Her’s version of LA urbanism is inching closer to reality.

Last month, I wrote a story for CityLab offering what I hope is a comprehensive view of LA’s massive transit development program. I tried to convey a sense of what these plans will mean for daily life in this famously car-centric city.

If all goes according to plan, when the world turns its gaze on Los Angeles in 2028, transit journeys that are a slog today will be a breeze. UCLA to USC for a football game; daily commutes from East LA to Century City; dinner in Santa Monica before catching a flight out of LAX; all will be possible — reasonable, even — by rail.

Even though my editor generously allowed me to exceed our target word count, there was still so much I couldn’t mention. I can’t emphasize enough how vast and ambitious LA’s transit plans are. There’s simply nothing like it anywhere in the US. (Seattle’s plans are impressive, too, but still a distant second.)

The brand new Regional Connector subway, which consolidated three light rail lines into two, and created three new subway stations in downtown LA, served as the peg for the article. I was only able to gloss other major projects:

Now the region’s most transformative projects are approaching fruition. Next year, Metro plans to open its first direct rail connection to LAX, which will connect the recently opened K Line to the airport’s forthcoming automated people mover system. The Wilshire Boulevard subway, now called the D Line, will open in phases starting in 2025, connecting downtown to Beverly Hills and UCLA.

Other planned projects are almost too numerous to name. Light rail lines and extensions are coming to the east San Fernando Valley, the San Gabriel Valley, parts of southeast LA and the South Bay. Planning is also underway for an extension of the K Line from Crenshaw in south LA to West Hollywood, and a new rail line through the chronically congested Sepulveda Pass.

It’s worth dwelling on the latter two projects for a moment. These two lines will likely be among the most significant transit projects in the country over the next couple of decades. And they’re exactly the kinds of projects we should be building a lot more of, instead of meandering surface-level light rail extensions that are slower than driving from day one.

The Sepulveda line and K Line extension will travel through densely populated neighborhoods, along very busy existing transportation corridors, and, as a result, will provide mind-boggling travel time savings that will make transit a no-brainer choice.

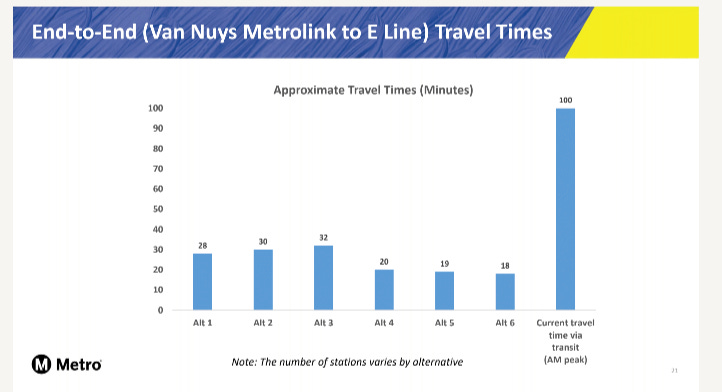

To Metro’s credit, they’re highlighting speed and travel time reductions in their community outreach. These two graphs, from a presentation on the Sepulveda Transit Corridor project, are worth a thousand words:

100 minutes vs. 18 minutes? Call it the annihilation of space by time. It’s something transit has been quite good at for nearly 200 years. And it’s something that, at this point in urban history, only transit — not electric cars, not autonomous cars — can achieve, as I highlighted in my piece on Caltrain electrification.

The K Line extension to West Hollywood would be similarly transformative, cutting travel times by half or more through the most crowded parts of LA, and providing a much-needed north-south transit option across the city.

Both of these projects face contentious decisions in the very near future.

Officials will soon need to choose between monorail and heavy rail subway technology for the Sepulveda project. Most transit advocates view the faster, higher ridership, and more expensive subway option as the superior choice, but powerful community groups in the San Fernando Valley and Bel Air are agitating for the monorail.

As for the K Line extension, officials will need to decide between a straighter, faster route alignment, or a slower, curvier alignment that hits all of the major job and population centers in West Hollywood, including the Sunset Strip. This is a toughy. Transit best practices usually call for lines that are as straight and fast as possible. But it’s also valuable for once-in-a-generation transit projects to serve as many major destinations as they can.

Metro projects that the curvy San Vicente alignment will serve the most riders. And the city of West Hollywood appears willing to contribute extra funds to break ground on this project sooner, if it follows the San Vicente alignment.

There are, believe it or not, several more major transit projects in the works in the LA area.1 These projects aren’t necessarily being developed by LA Metro, don’t always use traditional rail transit technologies, and, in at least one case, may not be a good idea at all.

The Inglewood People Mover will connect the K Line to SoFi Stadium, home of the Chargers and Rams and Taylor Swift, and the Intuit Dome, future home of the Clippers. The project has cobbled together a significant amount of funding, has widespread political support, and appears well-positioned to win the federal grants it needs to break ground. The goal is to get this system up and running for the 2028 Olympics.

This project is being led by the city of Inglewood, where the stadiums are located. The people mover will provide much-needed transit access to these two stadiums and their adjacent mixed-use developments. But with so much of the economic benefit of this project flowing to billionaire sports team owners, it’s worth asking why it’s being publicly funded. Especially when, across town, another sports-oriented transit project is being built with private funds.

The Dodger Stadium Gondola would link Union Station in downtown LA to Dodger Stadium in Elysian Heights, with an intermediate stop at Chinatown/ LA State Historic Park. The project, dubbed LA Aerial Rapid Transit, is being led by former Dodgers owner Frank McCourt. It’s also seeking to open before the 2028 Olympics, and is supposed to be privately funded, though it’s possible it will need some public funding as well. The gondola has encountered opposition among Chinatown residents, and LA Mayor Karen Bass has not said whether she supports the project. Final approvals — or disapprovals — could be coming soon.

Gondolas are a common form of transit in mountainous regions across the world, from Switzerland to Portland to Mexico City. This would be a great location to demonstrate next-generation aerial transit in America. The gondola would obviously provide a huge benefit to the Dodgers and their fans, cutting down on notorious gameday traffic and providing a spectacular transit alternative to the ballpark. It should also be a boon to LA Metro ridership, linking the transit system’s Union Station hub to the stadium. But even on non-game days, the gondola would be an awesome recreational amenity, providing easy access from the urban core of LA to the rugged open spaces surrounding the ballpark in Elysian Heights. Anyone who has endured the weekend crowds on the Roosevelt Island Tram in New York can easily picture how popular the LA Gondola would be.

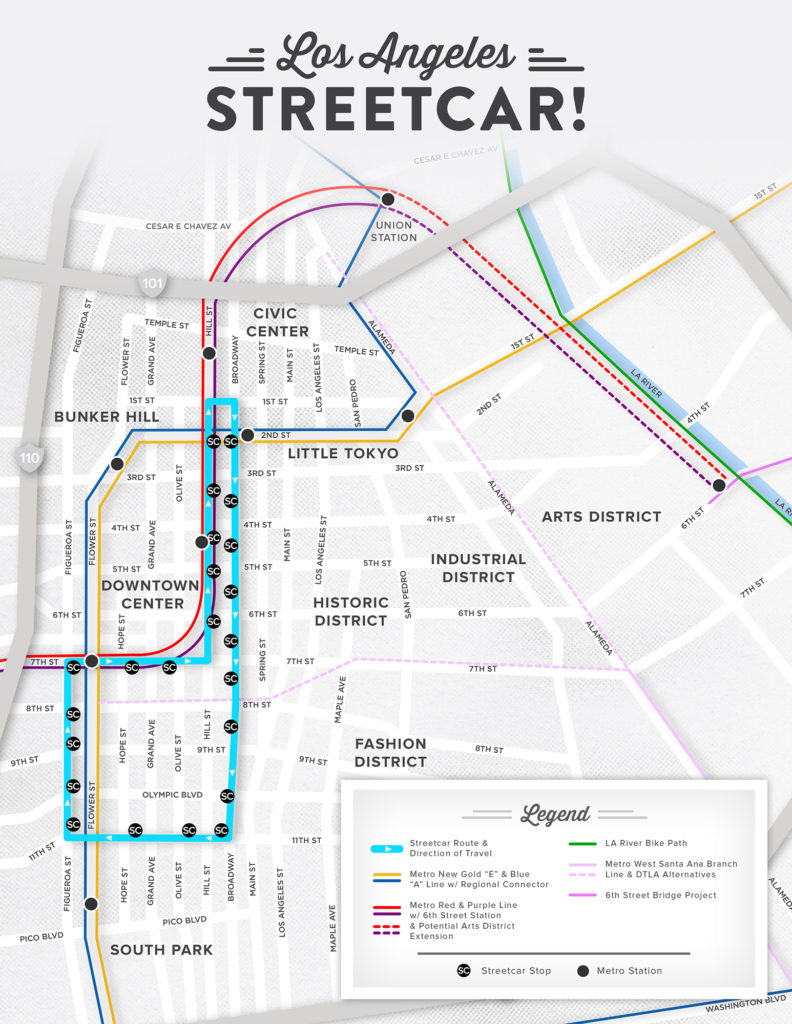

The Downtown LA Streetcar is a proposed 3.8 mile loop around the city’s downtown. Its route would form a big dipper shape, with a square section along the edges of South Park and a tail running through the Historic Core up to the Civic Center, and back again. Though seldom discussed in local politics or media, the project has significant local funding commitments and is moving through the federal funding process.

Downtown streetcars are already a dubious proposition, typically acting more as a real estate amenity and tourist attraction than a useful transit service. Downtown streetcar loops are worse, becoming a glorified theme park ride covering very little distance. And downtown streetcar big dippers are even harder to justify. Walking would probably be faster than many potential trips on this route. Biking would certainly be faster.

LA’s bikeshare expansion aspirations offer yet another reason to steer clear of small, slow transit projects. Metro recently put out a request for proposals soliciting a new operator for its bikeshare system. A system on the scale of New York’s Citibike would be a huge boon to the city’s growing transit network, providing easy first mile/ last mile connectivity to stations.

Congestion pricing, soon to become a fact of life in New York, could be coming to LA in the coming years, as well. LA Metro is currently studying three potential congestion pricing zones for its thoughtfully phrased “traffic reduction study:” Downtown LA, the I-10 Freeway, and the Santa Monica Mountains. Metro staff will present their recommendations to the Board on which option to pursue in the first half of next year.

Metrolink, Southern California’s commuter rail system, has big improvements in the works through its SCORE program, including several projects to upgrade tracks for more frequent service and higher speeds. The Antelope Valley Line connecting Santa Clarita and Union Station this month returned to hourly service, and the San Bernardino Line is expected to see service every half hour by 2028. The latter improvements would be essential to connect LA proper with Brightline West, the planned high-speed rail line between Rancho Cucamonga and Las Vegas. Any day now, Brightline could learn the result of a federal grant application that would enable the project to break ground, with an ambitious projected completion of 2028.

Link Union Station, another regional rail project in the works, will add through-running tracks to LA’s central train station. The project, funded in part by the California High-Speed Rail Authority, would eliminate the need for trains to terminate and turn around at Union Station. Instead, trains could roll right through, saving gobs of time on Amtrak’s Pacific Surfliner and creating the potential for a completely reimagined Metrolink map, with trains running east west and north-south across the breadth of Southern California. The project is largely funded and designed, but has faced numerous delays finding a contractor and beginning construction.

There are many, many more challenges facing all of these projects and the broader LA Metro system, some of which are enumerated in my CityLab piece.

But I think it’s important not to lose sight of the big picture. LA is building transit like crazy. Some of these projects, if done right, would provide sci-fi level technological leaps to the urban experience. They merit at least as much attention as whatever Cruise and Waymo are up to.

For a cool visualization of LA Metro’s entire existing, planned, and possible system, check out this Medium post by Adam Paul Sussaneck.

This is a great overview of the different transit lines & modes abuilding and planned for LA County. Plus your commentary on the usefulness and potential funding sources for the planned lines. I am now a subscriber!