The perils of freeway caps

Covering freeways with parks is the hottest trend in urban planning. Is it an elegant solution or a “Band-Aid over a huge wound”?

The Big Dig is having a moment. It has been nearly two decades since this massive urban freeway burial — but not funeral! — was completed in downtown Boston. It’s the subject of an excellent, in-depth podcast series that explores why this project was so damn arduous, and why it’s so hard to build big things in American cities.

And now, more and more cities are considering their own mini-versions of the Big Dig. Despite its high costs and myriad challenges, the Big Dig presents a tantalizing template. Freeway caps or tunnels offer the possibility of reconnecting and beautifying neighborhoods without reducing traffic flow or car access. But even as they ameliorate some of the surface-level issues with urban freeways, they don’t solve the deeper problems that come with routing thousands of cars through dense neighborhoods.

In my latest piece for CityLab, I wrote about one such freeway burial: The Kensington Expressway project in Buffalo.

This three-quarter mile cap over a freeway trench on the East Side of town is the marquee project of the Biden Administration’s Reconnecting Communities program, which was designed to heal the harms that urban freeways inflicted upon communities of color. Following three decades of community advocacy, the project is finally on the cusp of being approved.

But in recent months, there’s been a groundswell of opposition to the project from community members. My story has all of the details. India Walton, an East Side resident and former candidate for Buffalo mayor, conveyed the gist when she described the freeway cap as a “Band-Aid over a huge wound. It doesn’t go far enough, and I mean that figuratively and literally.”

The Kensington Expressway saga could be an inflection point in the ongoing debate about what to do with America’s urban freeways. There’s no longer any question as to whether this infrastructure is toxic and racist. That’s been acknowledged, in less pointed terms, by the highest authorities in the land. The question is the extent to which the nation is willing to rethink urban freeways and urban transportation networks more broadly.

Freeway caps tend to be more politically palatable than full-on freeway removal projects. In places with very high traffic volumes — into the multiple hundreds of thousands of vehicles per day — a freeway cap is probably the best solution on offer. Klyde Warren Park in downtown Dallas is a good example of a freeway cap that couldn’t conceivably have been swapped with a full removal. Same thing with the planned “Stitch” project over I-85 in downtown Atlanta, or the proposed caps over the Cross-Bronx Expressway. The most elegant freeway cap project I’ve seen is Doyle Drive in San Francisco, which created the Tunnel Tops park and completely transformed the urban experience of the Presidio.

Ray Delahanty, AKA CityNerd, has a good roundup of (mostly) successful freeway caps on Youtube:

But when it comes to freeway stubs; short, redundant corridors; or relatively low traffic areas, freeway tunnels and caps can represent a failure of the imagination. Seattle’s $3.5 billion Alaskan Way tunnel project is less than a mile from parallel I-5. Kansas City decked over part of a freeway in a downtown that is lousy with freeways, and it may deck over even more as part of a new stadium for the Royals. DC’s Capitol Crossing project is rapidly rendering invisible the I-395 stub. These are all improvements over the status quo. But they also, quite literally, entrench urban freeways for generations to come, foreclosing more ambitious visions of a future with fewer freeways, not just nicer freeways.

In other cases, freeway caps are presented as a fig leaf to the community as part of otherwise harmful projects — a tactic known as “greenwashing.” Megan Kimble goes deep into this dynamic in her excellent forthcoming book City Limits: Infrastructure, Inequality and the Future of America’s Highways. She describes how TxDOT is essentially dangling the prospect of small caps to justify ginormous, destructive freeway expansions through the middle of Austin and Houston.

With the cost of freeway caps as high $1 billion or more — to say nothing of the Houston and Austin freeway expansion projects, which are approaching $10 billion — it’s worth making like Buffalonians and asking whether this kind of investment is worth the cost. Expanding freeways, or entrenching them, or demolishing them does not take place in a vacuum. As Kimble’s book shows, these choices affect people’s decisions related to where they live, where they work, and how they get around. They affect the viability of transit, and the politics of housing.

San Francisco’s old housing policy regime was a world-historical failure. What comes next?

When I was a reporter at the San Francisco Examiner, I made it my mission to keep up with the city’s rapidly shifting housing policy. It remains an impossible task. Things…

But in America, our transportation planning and funding institutions aren’t set up to take this long view.

One of the most poignant aspects of the Kensington Expressway project is its total neglect of transit alternatives. On the project’s FAQ page, in response to a question about why transit was not included in the project, NYSDOT writes:

“The Niagara Frontier Transportation Authority (NFTA), the only organization with the authority to propose mass transit projects, is not currently proposing rail service in the transportation corridor.”

In other words, the state department of transportation has no jurisdiction over, and seemingly no interest in, transit. In fact, one of NYSDOT’s mandates in developing the project was to “maintain the vehicular capacity of the existing corridor.” Any concept that didn’t put cars front and center was doomed from the start.

This same mentality defines the I-35 expansion project in Austin, which is being developed completely in isolation from the city’s planned light rail system. In fact, the project’s traffic modeling for 2050 didn’t take this transit system into account at all.

The State-Sanctioned Urbicide of Austin

Earlier this year, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Lawrence Wright published a feature story in the New Yorker entitled, “The Astonishing Transformation of Austin.” It was the latest and most ambitious contribution to the flourishing sub-genre of urban change journalism. …

These outcomes are symptoms of the fact that most state departments of transportation are actually just highway departments, single-mindedly focused on the rapid and efficient movement of as many cars as possible.

As long as caps are viewed as the gold standard for fixing urban freeways and reconnecting communities, state DOTs will be able to continue in the same lane. Full freeway removal projects would put these agencies on a whole different track.

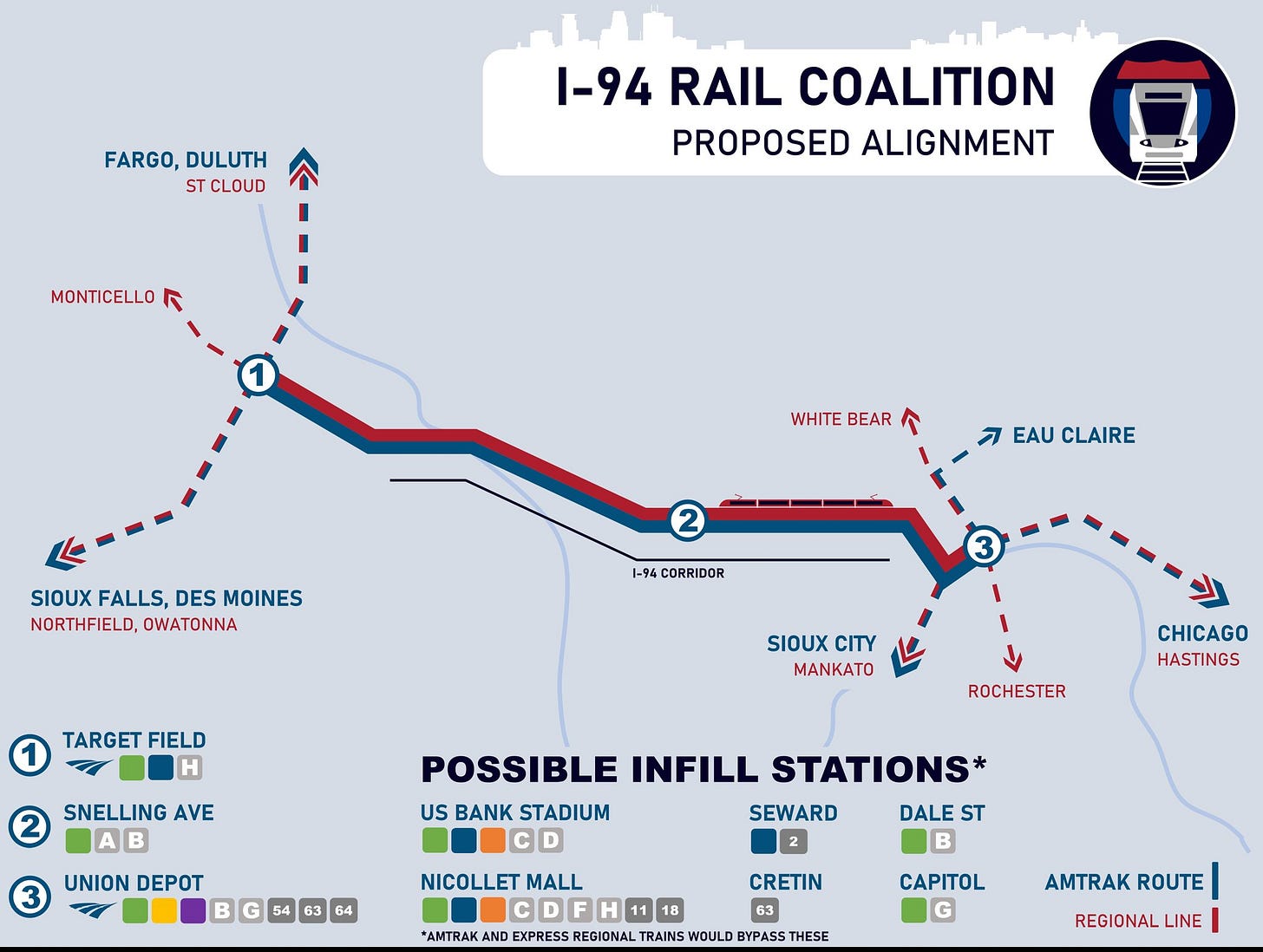

That’s what officials in Minnesota are beginning to consider for I-94 between Minneapolis and St. Paul. Once slated for a freeway cap, I-94 is now being looked at for a new rail connection between the Twin Cities, which could serve as the backbone of a reinvigorated regional and inter-city rail network.

Perhaps Minnesota leaders have looked back in urban history, and seen how the two most successful transit systems of the post-interstate era, BART and DC Metro, were built in the wake of major freeway revolts. Transit thrives in the absence of urban freeways, and it struggles amidst a glut of urban freeways. It’s a bit like Harry Potter and Voldemort: Neither can live while the other survives.

The Magic of Electrified Trains

A remarkable technology is about to make transportation in Silicon Valley much faster, much more convenient, and much more environmentally friendly. I’m speaking, of course, about electrified trains. Unlike electric cars, autonomous cars or highway expansions

Here in Austin, I-35 is a huge barrier that cleaves through downtown. Along its edges, vibrant, dense, walkable neighborhoods suddenly collapse into gas stations and strip malls accessible only by car. The sporadic caps would be aesthetically nicer than the highway itself, but they are likely to serve as a visual cue to the vast, barren wasteland in the heart of our city. At this point, since groups like Reconnect Austin, Rethink35, and others have visualized what the possibilities of a more imaginative project could be, one has to think that is not a failure of imagination on TxDOT's part but a lack of will, interest, or perhaps governing principle.