Will the Reconnecting Communities program survive Trump?

A freeway cap in Portland, Oregon is in jeopardy. But the visionary “restorative redevelopment” next door goes on.

For the past year, I’ve been reporting a longform article for Places Journal on the Biden administration’s most ambitious freeway fix, the Rose Quarter Project in Portland, Oregon. The marquee project of the Reconnecting Communities program would put a four-acre cap over I-5 in the Lower Albina District, a historically Black neighborhood that was devastated by the construction of the freeway and other urban renewal projects in the 1960s.

[Read the story here.]

By all accounts, Oregon’s $450 million Reconnecting Communities grant award was made possible thanks to the support of the Albina Vision Trust, a community organization turned non-profit real estate developer that plans to build a new neighborhood on the land their elders were pushed off of decades ago. The group has methodically built power since its founding in 2017, signing agreements with many of the major landowners in the area, breaking ground on a 94 unit affordable housing complex, and purchasing the historic apartment building next door. Capping the freeway, and eliminating a dangerous offramp into the neighborhood, are prerequisites for making this area livable again.

Albina Vision Trust’s plan to “buy back land, rebuild community, and reroot Black legacies and Black futures” was a perfect compliment to the Reconnecting Communities program. Created through the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act for the “removal, retrofit, or mitigation,” of highways that divided neighborhoods, the program was the first federal policy to specifically address the racism that went into the buildout of the Interstates. Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg regularly tied the program to racial justice in public statements, prompting much mocking from conservative media.

But for the Oregon Department of Transportation, this Reconnecting Communities project is inextricably tied to an expansion of the underlying highway. That’s something that environmental advocates in Portland can’t abide, leading to years of protests and lawsuits. All of these different considerations and constituencies have made the Rose Quarter Project exceedingly politically complex and expensive.

And now there’s another twist. Immediately upon assuming office, President Trump issued executive orders making terms like “racial justice” and “climate change” verboten at federal agencies. As Trump continues to undo as much of Biden’s legacy as possible, Republicans in Congress are poised to eliminate most of the funding for the Reconnecting Communities program with their “Big, Beautiful Bill.” That leaves the Rose Quarter Project — and this entire program, which was funding flawed yet potentially transformative projects from Buffalo to New Orleans — more uncertain than ever.

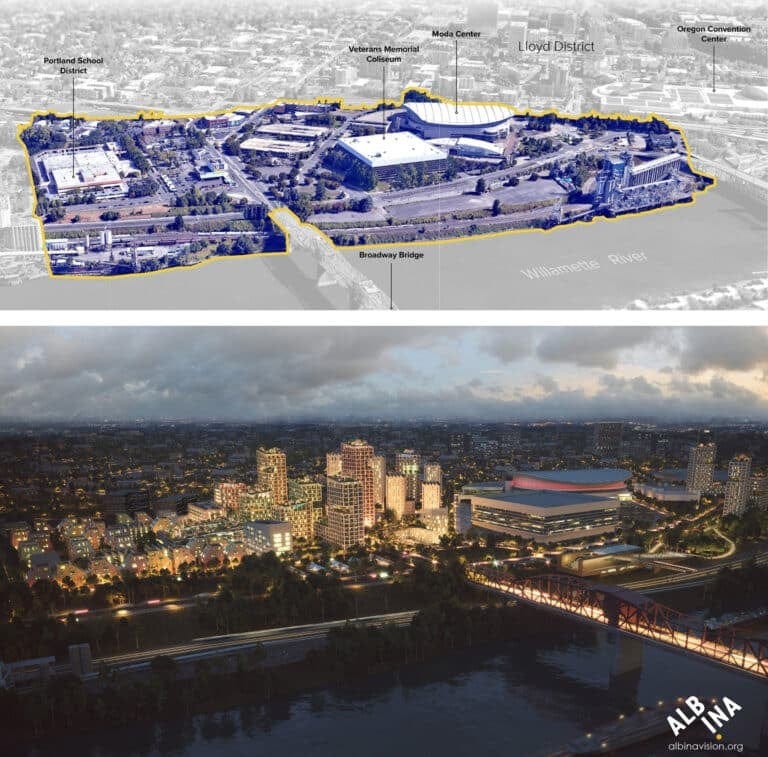

No matter what happens with the Rose Quarter project, the work of the Albina Vision Trust goes on. The long term plan is to build 3,000 mixed-income, “climate-positive” homes on 94 acres just across the river from downtown Portland. Their first building, Albina One, will begin welcoming residents this summer. Next on the agenda is the redevelopment of the 10 acre Portland Public Schools administrative building, a brutalist fortress that could become as many 1,000 homes.

Albina Vision Trust’s model of “restorative redevelopment” seems like a promising extension of the nascent social housing movement, tailored to the American context. It’s especially relevant as cities seek more intentional ways of rebuilding public housing complexes and other places where the legacy of racist urban planning decisions loom large. I’ll have some more thoughts on this in a future post.

In the meantime, I invite you to read my article in Places Journal’s Rethinking the Interstates series. The piece goes deep into the story outlined above, connecting this particular project to the history of freeway construction and freeway removals in the US. It also features a number of lovely people who showed me around Portland and shared their hopes for the city’s future.

Begging your pardon, but I live near the Broadway/Weidler corridor and abhor the existing traffic hazards that will worsen with the RoseQ I-5 so-called "improvement" as proposed. ODOT is pulling another stunt on the regular people of Oregon; a clear example of Waste, Fraud, Abuse. Only a few elements of the proposal are salvageable. ODOT does not have a credible plan to show the public. Period. ODOT/WsDOT spent $190M over 9 years on the I-5 CRC Bridge peer-reviewed design rejected as "structurally unsound." PDC could also be called out for grandiose development notions. Not enough money for Parks AND Police. Plenty of money for a new waterfront ball park-o-rama. Main problem: People don't enjoy living anywhere near freeways and hectic freeway bound traffic.