Can California High-Speed Rail make it to the Bay?

The project notched a major victory by securing long-term funding. But getting the line to major population centers remains an enormous challenge.

In 2019, California Governor Gavin Newsom used his first state of the state address to “level about the high-speed rail.” The Los Angeles to San Francisco project “would cost too much and, respectfully, take too long,” he said.

The 2008 ballot initiative that kicked off the project promised a 2 hour 40 minute high-speed rail journey between San Francisco and LA funded by a $10 billion bond. Those travel time requirements, combined with that level of initial funding, had made the full project practically impossible to execute.

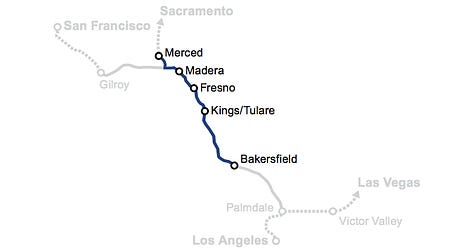

Since Newsom’s speech, the state has focused its energy and funding on a 170-mile section in the middle of the route connecting the Central Valley cities of Merced and Bakersfield.

Now, the newly instated CEO of the California High-Speed Rail Authority, Ian Choudri, is imploring Newsom and the state legislature to reverse course. Choudri is publicly airing what has been intuitively obvious to anyone with the vaguest sense of the state’s geography: Merced to Bakersfield is not a great high-speed rail corridor. A politically and economically viable system needs to connect the state’s major population centers, as voters were promised in the 2008 ballot initiative that initiated the project.

Choudri has succeeded in one part of his mission: Getting the state to extend its funding commitment to the project to the tune of $1 billion per year through 2045. But that’s just the start.

Choudri has asked the state government to consider a new plan that would expedite connections to the Bay Area and Los Angeles area using private funding. While he’s at it, he has put out a laundry list of procedural reforms—piggybacking off of the ascendent abundance movement popularized by Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s bestselling book—that could grease the wheels of a project notorious for delays.

It could be a do-or-die moment for California-High Speed Rail. The Trump administration is seeking to claw back over $4 billion in grants, and Republicans in Congress have made clear that no new federal funds will be forthcoming as long as they’re in power. (The authority is fighting the administration’s funding clawbacks in court.)

“The program is now at its crossroads,” Choudri said at a press conference in August. “We can choose to let the challenges of the past define the program's future, or we can meet the moment by supporting high-speed rail with the right tools and partnerships to make the kind of meaningful progress we all want to see.”

Choudri has been talking about making major changes to the project since shortly after he took the CEO job a year ago. In August, the California High-Speed Rail Authority offered the most detailed look at what those plans could entail in a published report.

The 2025 Supplemental Progress Update Report states that the current project, connecting Merced and Bakersfield could be completed by 2032 at a cost of $37 billion. But it would be saddled by an ongoing operating deficit of at least $30 million annually, violating the terms of the 2008 ballot measure, which requires the project not to receive operating subsidies. That deficit would also make it impossible to bring in private investor partners.

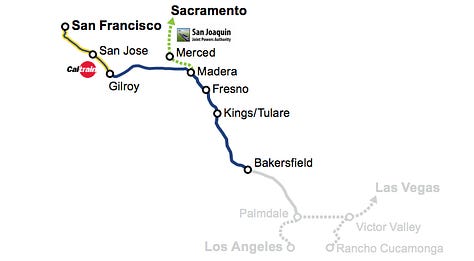

By contrast, the report finds that a route connecting Bakersfield and Gilroy, on the rural fringes of Santa Clara County, would generate an operating surplus of roughly $300 million. Under this plan, high-speed trains would continue up to San Francisco on tracks shared with Caltrain. Construction would cost $54 billion—not including an additional $3-$6 billion to electrify and improve Union Pacific-owned tracks connecting Gilroy and San Jose—and be complete by 2038.

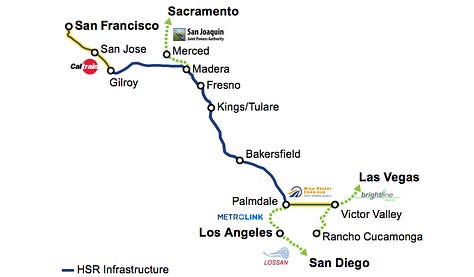

An additional connection from Bakersfield to Palmdale, where riders could transfer to local trains for Los Angeles or, potentially, to Brightline trains bound for Las Vegas, would generate an even greater operating surplus, of over $600 million annually. Combined with the section up to Gilroy, this scheme would cost a total of $87 billion and could also be ready by 2038.

Those operating surpluses could be used to pay back investors over time, or to fund future extensions of the line.

All of these scenarios would be value-engineered to be cheaper and more feasible to construct than previously envisioned. The railroad would be designed to handle steeper grades and sharper turns, limiting the expensive tunnels and viaducts that would be needed. Stations would be far smaller and less elaborate.

Choudri also hopes to maximize other revenue streams, like building transit-oriented development around stations, using railroad corridors for fiber optic cables and electrical transmission lines, selling clean energy, and even building AI data centers.

To do this, and build the railroad, the authority wants more power to streamline its own activities through permitting reform. These proposals build off of the abundance-inspired California Environmental Quality Act exemptions the state legislature passed earlier in the year, one of which specifically exempted high-speed rail stations and maintenance facilities from environmental review.

Another permitting reform bill that would have allowed neutral third parties to provide construction permits and capped the amount of time such permits would be allowed to take died in committee last month. A different bill that would empower the authority to capture profits from transit-oriented development was also held in committee. Both bills could return next year.

However, the project scored a major victory this month, when the state legislature and Newsom agreed to extend California High-Speed Rail’s share of Cap and Trade funds through 2045, ensuring the project will receive $1 billion per year in funding. It is the single largest funding commitment the project has received in its history.

With this consistent revenue stream, Choudri believes private investors will come calling to help get the railroad out of the Central Valley. Over the summer, the authority received 31 responses to its request from private entities interested in getting involved in the project.

“The part of the community that came in a strong way was the equity partners,” Choudri said at the authority’s August 28 board meeting. The authority is continuing to have more detailed discussions with these groups.

Another potential model for partners is to put up an investment upfront, and then earn their money back by operating passenger trains, freight, or other services using the project’s infrastructure. This is done in many other countries, Choudri noted at the board meeting, and many of those same firms are among those that responded to the authority’s request for expressions of interest.

However, in his statement celebrating the Cap and Trade funding, Choudri also suggested that a greater financial commitment from the state would be needed to get the project out of the Central Valley. “We must also work toward securing the long-term funding—beyond today’s commitment—that can bring high-speed rail to California’s population centers, where ridership and revenue growth will in turn support future expansions.”

The Bakersfield to Gilroy to San Francisco plan appears to be the authority’s favored option going forward, though Choudri insists that it would be a building block to completing the entire system. The NorCal-first phasing, leaving the project over a hundred miles and a mountain pass away from Los Angeles, has historically been an impediment to securing LA-area politicians’ support.

This plan would also require other challenging maneuvers. It would nix the city of Merced from the route after years of big promises, angering leaders there. It will also require negotiating with Union Pacific, and identifying additional funds to upgrade the stretch of track it owns between Gilroy and San Jose. (In a statement, Union Pacific said it had previously discussed sharing track with California High-Speed Rail along that segment, and is open to continued discussions.) And it would require a repeal of a 2022 law that limited spending outside of the Central Valley.

The pivot may even contravene the terms of the 2008 ballot initiative. As California Policy Center fellow Marc Joffe has observed, the slower travel times on that Gilroy to San Jose segment could render the total San Francisco to Los Angeles journey impossible to make in under 2 hours and 40 minutes, violating the ballot initiative language.

Making matters even more complicated, the federal grants that the Trump administration is attempting to cancel are specifically earmarked for the Merced-to-Bakersfield segment. Pivoting away from that concept could imperil the authority’s legal case that it is entitled to those funds.

Joffe, a longtime California High-Speed Rail critic, believes the best way forward for the project is a new ballot initiative laying out a more manageable project, roughly in line with what Choudri is currently proposing. With recent polls showing Californians remain broadly supportive of the project, that could be a winning proposition.

What’s undeniably clear is that Choudri is finally “leveling” about the project in a way no public official has done. He’s not simply pointing out the overambitiousness and underfunding of the initial concept, but he’s also laying out more modest steps that could get a useful project up and running “in our lifetimes,” in his words. That means reckoning with the morass of procedural obstacles that have turned practically every lawsuit and permit into a delay, and the overdesigned stations and track structures that the project blithely pursued despite the escalating costs.

Instead of shooing away private sector partners, as the authority has done in the past, Choudri is welcoming them in with the humility that outside entities might know a little bit more about building high-speed rail than a state agency with no prior experience.

Perhaps, the Trump administration's threats are having a focusing effect for everyone involved. Newsom, hero of the anti-Trump resistance movement, would be loathe to concede defeat to the president on the state’s signature infrastructure project. Democrats skeptical of the project are probably going to be wary of aligning themselves with Trump.

The abundance movement has offered a new vocabulary for liberals to support cutting red tape for projects like this one. Indeed the book Abundance cites California High-Speed Rail as the epitome of liberal governance gone wrong. Choudri’s fixes for the project look like they came right out of the abundance playbook.

The tides have turned. The question is whether it’s too little, too late.

This article originally appeared in Fast Company. It is republished here with permission.

PS: For more California High-Speed Rail content, check out this video I did for Planetizen:

A lot of good information here.

If the Authority decides to forgo going to Merced and instead focuses efforts on connecting the Central Valley to San Francisco via Gilroy and San Jose, a wye at Chowchilla (Fairmead, actually) would no longer be required. A substantial amount of money could be saved just from that change alone. With that change implemented, it would be prudent to put in a station at Fairmead at the intersection of State Routes 99 and 152. As such, this would allow patrons to board — and alight from — high-speed trains in lieu of their boarding — and alighting from — such at Merced. It would be a little more inconvenient for Merced residents and others, but would still allow all persons affected reasonable access. If the plan was to connect Bakersfield with San Francisco (a most doable part of Phase 1), I don’t understand why the big todo about getting Merced connected.

As to your comment about not being able to meet the 2 hour 40 minute LA-SF scheduling commitment, for an express, non-stop trip, by the way, that, too, is doable by my calculations.

Breaking it all down, what we’re dealing with is a 464-mile total Phase 1 (LA-SF) distance. Meeting a 2 hour 40 minute scheduling commitment seems most achievable. Required, though, as I see it, would be a 30-minute run between San Francisco and San Jose, a roughly 50-mile distance. To allow the train to make that kind of time, speed would need to be an average 100 mph, a scheduling commitment not out of the realm of possibility.

That would leave the 30 miles between San Jose and Gilroy. The presumption is trains would run here at at least 110 mph. If pushed up to 120 mph, trains could complete that segment in 15 minutes. Now assuming a 180-mph train speed here is permitted, if I calculated correctly, the San Jose-Gilroy run could be made in, what, 10 minutes? Total trip time for those 80 miles is now down to 40 minutes. A non-stop, express train, therefore, operating at an average speed of 192 mph the rest of the way, the train then would meet its scheduling goal. I don’t believe that to be out of the realm of possibility either even with having to construct track through two mountain passes. Remember: top speed on tangent track is 220 mph. Long, gentle curvature and tangent (straight) track in the Valley will allow for this.

And, finally. Running high-priority high-speed freight trains, even if mixed in with high-speed passenger trains is a great idea. If not that, they could operate at night when no high-speed passenger trains would presumably be operating.

They should definetly try and cheap out as much as possible, like building single tracked only leaving space for more tracks reserved, using highway medians when possible, aiming for 250kph instead of 300+kph allignments, etc. Everything that can be done to get trains running to either SF or LA as soon as possible, should be done.