California High-Speed Rail's plan to right itself

The railroad's new CEO thinks he can get the project back on track. The stars will need to align this summer.

These are dark days for California High-Speed Rail.

Construction in the Central Valley has been far slower and more expensive than anticipated, thanks in part to questionable decisions made in the early phases of planning. The Trump Administration is seeking to claw back over $3 billion in federal grants. Additional federal support is unthinkable in the immediate future.

But there may be a ray of hope. The California High-Speed Rail Authority, under new CEO Ian Choudri, is beginning to develop a plan to get the train back on track. The plan, in effect, is this: Secure private sector funding for the project backed by guarantees from ongoing state revenues. With those funds, the Authority would be able to extend the line out of the Central Valley, to the gateways of the Bay Area and Los Angeles metros, where riders could connect to regional trains bound for the major cities.

Choudri, who began as CEO last summer, laid out the plan at the Authority’s May 1st board meeting.

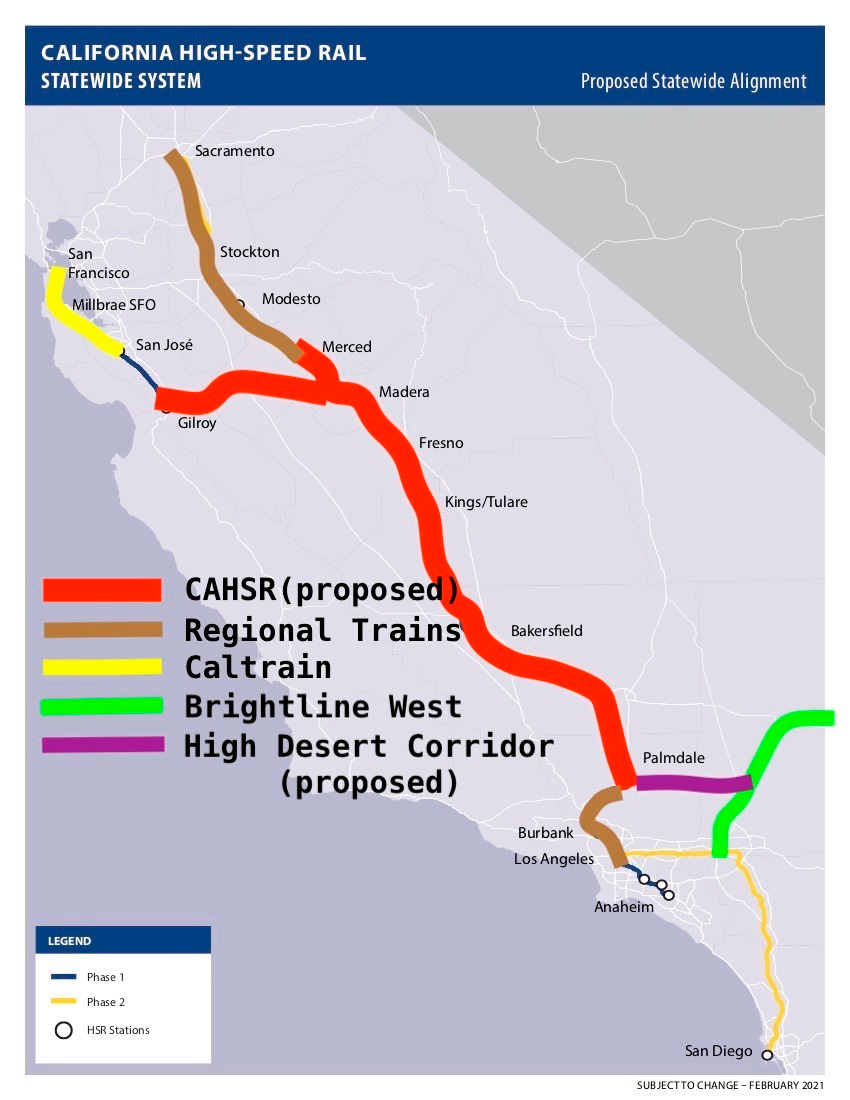

Since the beginning of the year, Choudri has been in conversation with potential private sector partners “almost on a weekly basis,” he reported. To attract investment, the project needs to deliver a rail system that goes beyond the extent of the under-construction Phase One line connecting Bakersfield and Merced. Reaching Gilroy, at the edge of the Bay Area, and Palmdale, at the edge of the LA area, “is the only scenario that works for the private sector investors,” Choudri said. “Getting out of the Central Valley and connecting it to the population centers is the most critical feature of this program.”

Those investors are looking for “backstop guarantees” from the state, he went on. Choudri’s team has proposed “several financial scenarios,” to staff members in the state legislature and Governor Gavin Newsom’s office. One potential funding source is the state’s Cap and Trade program, which currently provides California High-Speed Rail roughly $1 billion per year. Newsom recently announced his intent to extend Cap and Trade beyond its current 2030 sunset date, which could be a boon to the project.

Cap and Trade revenues, however, will not be enough money to complete the works Choudri has envisioned. “We are asking the [Newsom] administration to look at Cap and Trade as a source, but we’ll need more than that,” he said.

Choudri said he hopes to get this plan firmed up by the end of the summer, at which point the Authority will release revised cost and time projections. The only details he revealed, besides the Gilroy to Palmdale alignment, is that this system can be built in “less than 20 years.”

What does all of this amount to?

For one thing, it’s an acknowledgement that the current Phase One project in the Central Valley is not economically or politically viable as a standalone endeavor. With challenges looming on multiple fronts, the Authority needs to show a path to something resembling the project Californians were initially promised. In order to survive, California High-Speed Rail needs to demonstrate that it is, quite literally, going towards the liberal voters who actually want it and the traffic choked cities that desperately need it.

Choudri’s plan also seems to convey a sense of urgency. When Democrats are in power, there’s always a vague hope that the federal government will come through for high-speed rail in a big way. Not only has that possibility evaporated, it appears that the Trump Administration will do everything possible to undermine this project and high-speed rail more broadly.1

Another timely factor is the health of California's budget, which is highly dependent on the earnings of corporations and the ultra wealthy, and thus, the performance of financial markets. It could be much harder to get this deal done during a recession. Time is of the essence politically, as well. Though Newsom has not been the project’s best friend, he has dutifully stood by it. There’s no guarantee the next governor will do the same, or even that Newsom will do the same on the eve of the midterms next budget cycle.

If this plan goes forward, it will be interesting to see whether new opportunities emerge to run high-speed trains on existing track to San Francisco and LA proper. This is more feasible in the Bay Area, where a relatively short, flat stretch of freight-owned track lies between Gilroy and the electrified Caltrain tracks in San Jose. From there, high speed trains should be able to use existing track — albeit at slower speeds than planned for in the original system — up to downtown San Francisco.

Getting from Palmdale to LA on existing rails would be harder, since the tracks there are rickety, windy, and unelectrified. Barring major upgrades to the Antelope Valley Line, LA-bound riders would have to transfer at Palmdale to the diesel Metrolink train.

Another intriguing possibility, should this plan go through, is whether it could generate investor interest in the High-Desert Corridor connecting California High-Speed Rail and Brightline West, the under construction high-speed rail line between Southern California and Las Vegas. That missing link would provide a huge boost to both systems, potentially allowing high-speed trains to roll from the Bay Area and the Central Valley directly to Las Vegas.

It remains to be seen whether California High-Speed Rail will be able to secure the funding it needs at the state level, or whether it can withstand the economic and political maelstrom the Trump Administration seems hellbent on unleashing. But at least the new CEO is thinking creatively about solutions, trying to find some way to turn the voters’ wishes into reality.

In a previous article, I asked “Will Trump derail America’s bullet train plans?” The answer is, definitively, yes. Not only is he undermining the California project, as I anticipated, he has also cut off funding and ended an Amtrak partnership for a proposed project in Texas.

As I see it, the greatest marketing tool is to get trains running as soon as possible in the Central Valley between Merced and Bakersfield, otherwise known as the interim Initial Operating Segment (IOS) (as I remember it being called) on 171 miles of right of way first. Once that happens, and riders get to see firsthand the value and benefit(s) that “true” high-speed-train travel in the U.S. has to offer, said people and others will be “making” the clarion call (singing the praises, really) requesting, perhaps even demanding, the interim IOS of Phase 1 (L.A.-S.F.) system be significantly added on to. It’s what my gut is telling me.

The problem is that, with the Central Valley route -- and mixed-running near the cities will make this issue even worse --the project can't deliver the promised 2 hr 40 min trip between the downtowns of San Francisco and Los Angeles.

At this point, my view is that the federal government should abandon any further funding. California should abandon high-speed rail aspirations, for this particular project, and consider how the Central Valley infrastructure could be salvaged for regular-speed rail.

Perhaps, at some point in the future, true high-speed rail between Los Angeles and San Diego or Los Angeles and San Francisco straight up I-5 should be considered.

But this project is irredeemable as high-speed rail. The sooner Californians realize that, the better.