California High-Speed Rail’s original sin

Ezra Klein is right about many of the project’s problems. But he neglects its initial network design failures and what we can learn from them.

The wait is nearly over. Abundance is nigh. Next week, Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson will release their highly anticipated book laying out the principles of the “abundance agenda.”

I was able to snag a review copy of Abundance a couple of months ago. I found Klein and Thompson’s case for a political movement focused on building and inventing things that make people’s lives better to be very compelling. In particular, I appreciate the way they connect the built environment and urbanism to national politics. Our inability to build housing, transit, and clean energy aren’t just obscure, wonky topics for activists and bureaucrats to worry about. These are some of the fundamental political issues of our time that should concern everyone.

On Sunday, Klein released a New York Times audio essay promoting the book, in which he lays out his California High-Speed Rail case study. Having covered the project for years, I found Klein’s criticisms to be broadly correct, but incomplete.

The main issues Klein identifies with the project, in his audio essay and in the book, are the long environmental review process and its attendant lawsuits; eminent domain and property disputes; and the decision to begin construction in the San Joaquin Valley. These are all very real problems.

The points I would add have more to do with railroad network design and technology. California High-Speed Rail began with a route map and service plan driven more by politics than by railroading best practices. Planners promised an unrealistically advanced system that would reach the highest possible speeds and hit practically every populated region in California. From the start, California High-Speed Rail was an everything bagel, to borrow from Klein’s lexicon, with goodies for every conceivable constituency.

Had planners been more realistic and listened to railroad experts from other countries, they could have delivered more benefits to more people sooner. They also could have avoided many of the subsequent issues that Klein identifies by building on corridors the state already owns.

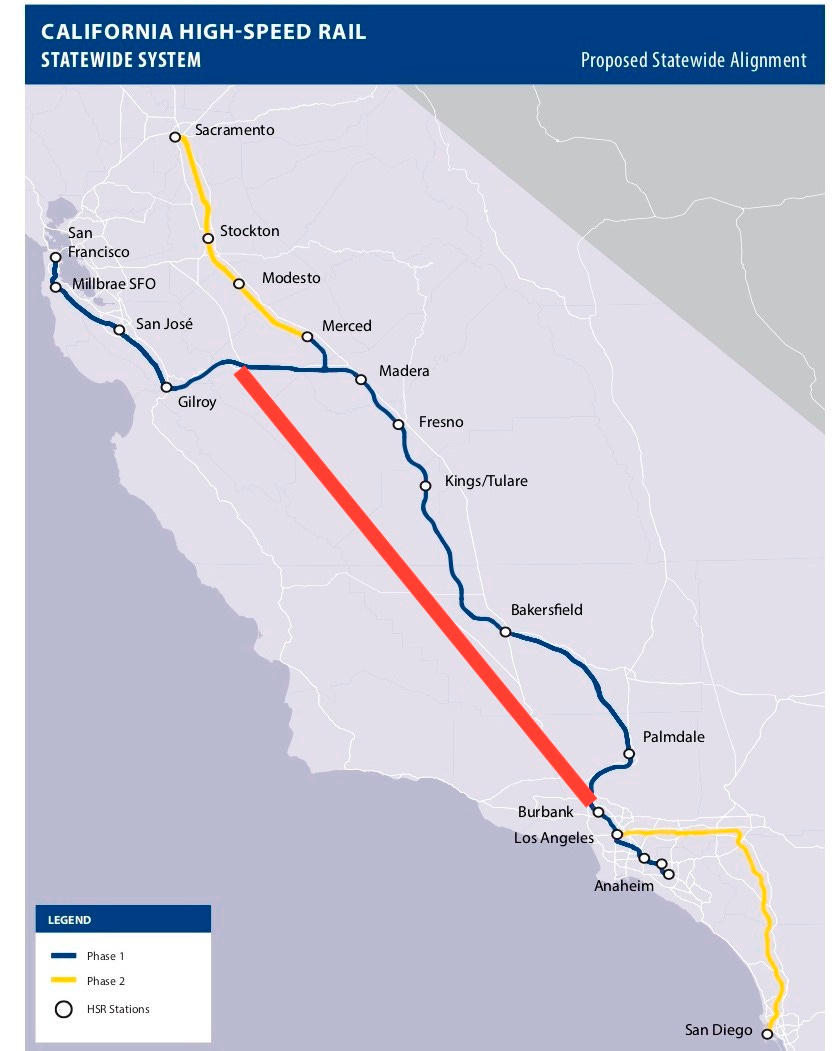

The 2008 high-speed rail plan approved by California voters required the train to travel from San Francisco to Los Angeles in no more than 2 hours and 40 minutes. At the same time, the project promised to serve the downtown of every major and not-so-major city in between, including Merced, Madera, Fresno, and Bakersfield in the San Joaquin Valley and the high desert city of Palmdale.

Those travel time promises, combined with that route map, meant that California High-Speed Rail would have to reach speeds of 220 miles per hour. In 2008, only a couple of trains in the world reached that speed, and it’s still the fastest any high-speed trains currently travel. Add in California’s mountainous, earthquake-prone topography, and you’ve set yourself up for one of the most difficult engineering projects ever attempted. All of this had to be accomplished by an agency, the California High-Speed Rail Authority, that had never built a single mile of track.

In other words, the project was set up for failure.

What could have been done differently? In the 2000s, the French national railroad firm SNCF courted California to plan and build its high-speed rail line. Based on its experience constructing the TGV high-speed rail system in France, SNCF advised the state to simplify its route map by travelling mostly on the I-5 corridor through the San Joaquin Valley and over the Grapevine into the Los Angeles area.

SNCF’s plan would skip over the cities in the San Joaquin Valley and the high desert. But it would make for a faster and more direct route between San Francisco and LA, with far fewer potential property disputes and complex track structures along the way. This concept was more likely to be profitable than the state’s plan, SNCF believed.

But once it became clear that California would not deviate from its initial route map, SNCF packed up and left.1 Instead, the company ended up building a high-speed rail line in Morocco that opened in 2018.

"It's like California is trying to design and build a Boeing 747 instead of going out and buying one," Dan McNamara, an SNCF civil engineer told the Los Angeles Times in 2012. "The capital costs are way too high, and the route has been politically gerrymandered."

Rebuffing SNCF’s advice, its assistance, and its investment will go down in history as California High-Speed Rail’s original sin. As Eric Goldwyn of the Transit Costs Project has argued, one of the most important pre-conditions for the success of a transit project is to copy from proven models. Buy a 747 off the shelf, don’t build one from scratch.

SNCF’s proposal was based on its own experience. The French national railroad built a profitable high-speed rail network by bypassing the centers of many secondary cities. This model avoids the expense and eminent domain battles of routing new rail lines through built up areas that offer a relatively small ridership base.

Italy pursued a different path to high-speed rail over the course of its “long modernization,” transportation researcher Marco Chitti writes. Instead of building out high-speed rail lines from scratch, it gradually upgraded its existing railroads. Over the course of decades, Italy smoothed curves for higher speeds, built new tunnels through challenging terrain, and added high voltage electrical infrastructure to power faster trains. By the 2000s, the sum of these improvements allowed Italy to begin running world-class high-speed rail.

There’s precedent for applying these lessons in the U.S. In Florida, a private company called Brightline went the Italian route by traveling along existing track through the urban core of the Miami area. It has made some upgrades to support speeds of up to 80 miles per hour on that section. Closer to its Orlando terminus, Brightline runs on newly built track that can support speeds of up to 125mph.

The company’s next project, the under-construction Brightline West system connecting Southern California and Las Vegas will go the French route, stopping short of the urban core of Los Angeles. Instead, Brightline’s high-speed trains will terminate in the suburb of Rancho Cucamonga, where riders will be able to transfer to regional Metrolink trains bound for LA. The system would undoubtedly be better if it went those additional 50 miles to LA Union station. But that would be exceedingly expensive and politically challenging.

Brightline West is actually doing what SNCF advised California to do: Travel in the right of way of an existing highway. Its route in the median of I-15 almost totally eliminated the utility relocations, eminent domain disputes and environmental lawsuits that vexed California High-Speed Rail. It also means Brightline West won’t be as fast as the fastest high-speed trains around the world. Current engineering documents show a top speed of 186 miles per hour, with long stretches of track maxing out at closer to 100 mph. Initially, much of the line will be single-tracked, making for a cheaper and quicker construction project, albeit with lower capacity.

Just about everything in Brightline’s toolkit is meant to reduce costs and improve the odds that the project will actually get built. It opts for a good enough project, rather than a perfect project. It’s a plain bagel, not an everything bagel. But plain bagels are better than no bagels. Orlando to Miami in 3 and a half hours is still a very competitive mode of transportation. SoCal to Vegas in 2 hours and 10 minutes will be a huge improvement on driving.

If California High-Speed Rail made the trip from LA to SF in, say, six hours, that would still revolutionize mobility in California, providing a comfortable, competitive alternative to driving or flying. It wouldn’t be the most advanced railroad in the world, but it would be good enough. Over time, with a growing base of political support, the state could make upgrades that could turn it into a world-class high speed rail line.

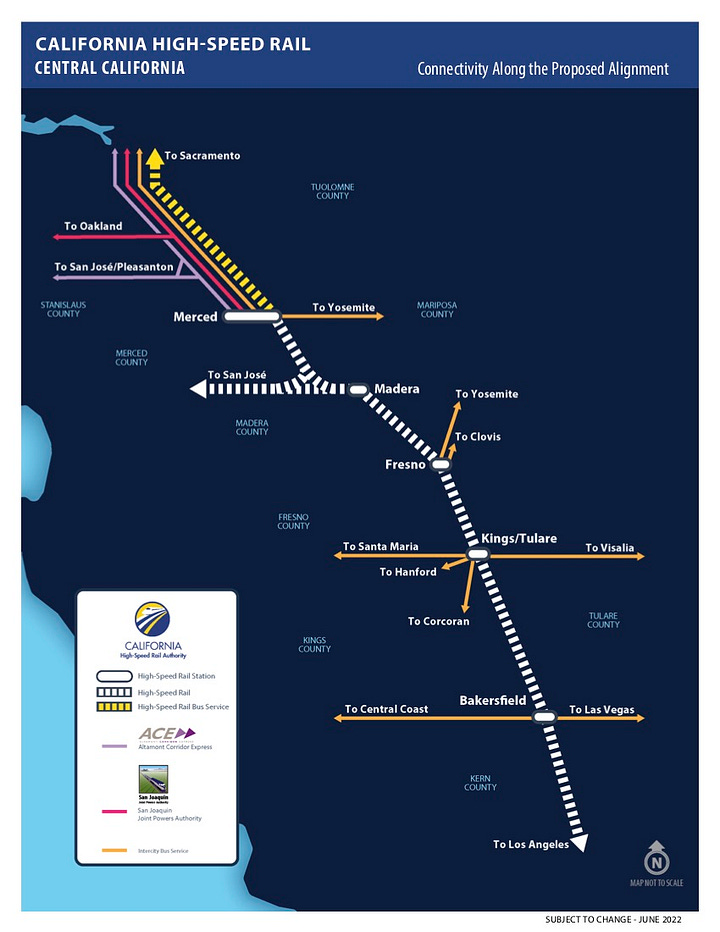

California is applying these lessons belatedly. It was well after the 2008 voter approved plan that the California High-Speed Rail Authority determined it would share track and right of way with Caltrain in the Bay Area and Metrolink in Southern California. The Caltrain electrification project completed last year, an initial step to prepare the corridor for high-speed rail, is already providing huge benefits. California’s latest state rail plan envisions the electrification of most of the state’s passenger rail lines, not just the core high-speed rail system.

More of these smaller, bookend projects upgrading existing rail infrastructure offer a means of completing an initial San Francisco to LA route — even given the path dependency of poor planning decisions from the past. The electrification and improvement of Metrolink’s Antelope Valley line, Northern California’s Altamont Corridor Express, and the under-construction Valley Rail line to Sacramento could get high-speed trains into the major cities on existing track.

The only missing piece is the Bakersfield to Palmdale segment over the Tehachapi Pass. California High-Speed Rail’s current leadership recognizes that this keystone project would create the potential for a Southwest regional high-speed rail network, connecting not only San Francisco and LA, but Las Vegas, as well.

Some might argue that the disciplining forces of capitalism have enabled Brightline to succeed (so far) where California High-Speed Rail has failed. But that theory doesn’t explain how state-owned companies built out high-speed rail networks in France, Italy, Japan, China, and just about every other country where this technology exists. This, I think, is one of the core insights of Abundance. Builders need to accept less-than-perfect projects when the alternative is no project at all, no matter who is doing the building.

Some California legislators viewed the French railroad’s involvement in transporting victims of the Holocaust as an impediment to working with the company. In response, SNCF offered its first official apology for its activity during World War II in 2010 as it pursued projects in Florida and California. While understandable, these kinds of demands are still more symptoms of everything bagel liberalism, where every aspect of a project must be politically, socially, and environmentally perfect. As another example, San Francisco just recently rolled back rules requiring city contractors to disclose whether they were involved in the slave trade.

I've been thinking of these kinds of things as the impossible bargain of feel good politics that leads to nothing at all. Very frustrating. Great article!

First, it would be great to have a terminus at Rancho Cucamonga because it's fun to say "Rancho Cucamonga," especially if you belt it out as the TV announcer would on Lucha Libre night.

"Instead, Brightline’s high-speed trains will terminate in the suburb of Rancho Cucamonga, where riders will be able to transfer to regional Metrolink trains bound for LA. The system would undoubtedly be better if it went those additional 50 miles to LA Union station. But that would be exceedingly expensive and politically challenging." There is so much that I don't understand about relative cost. What are the cost differences between engineering for conventional passenger rail and HSR, and are these differences magnified within populated areas? What speeds can HSR trains operate safely within populated areas? What are the passenger loads of an HSR train at Rancho Cucamonga compared to the passenger capacity on MetroLink?