We need to talk about ‘missing massive’ housing

In most neighborhoods, missing middle housing will do the trick. But right on top of subway stations, urbanists should think bigger.

First, some book news: On October 21st, I’ll be hosting a launch party for The Unfinished Metropolis with Abundance New York in Brooklyn. Members of the public can RSVP at this link — but note that capacity is limited! Stay tuned for info on more book events in New York, San Francisco, and possibly elsewhere.

My first stop on the podcast circuit was with Nothing But Respect, “the last uncompromised basketball podcast,” where we discussed stadium subsidies, Mike Davis’ infinite game, and why sports rivalries started with trains. Listen here.

Jersey City is a unicorn. It’s one of the only coastal cities growing like a sunbelt city. Over the past 15 or so years, its population has increased by 20 percent and its housing stock by 24 percent. But instead of growing out, as they do down south, Jersey City grew up.

Last month, I wrote about the political and economic forces that made Jersey City’s building boom possible for Vital City’s housing issue (which readers of this newsletter should absolutely check out). It’s not an unalloyed success story: There have been real growing pains and missed opportunities. But through its building boom, Jersey City has managed to retain its diversity, protect low-income tenants, add to its affordable housing stock, and create a more vibrant street scene. All the while, it’s done more than its fair share to address the housing shortage in the New York area.

In this post, I’m going to focus on the development pattern that Jersey City exemplifies. The majority of its new construction took place in two areas right next to PATH train stations: At Exchange Place and Newport on the Hudson River waterfront and at Grove Street and Journal Square some ways inland. These relatively small neighborhoods were able to add thousands of homes by permitting a couple dozen towers with hundreds of units apiece. (In fact, these Jersey City neighborhoods actually have higher-density base zoning than anywhere in Manhattan, where the tallest buildings are only possible because of “air rights” purchased from nearby properties.)

Niskanen Center housing policy analyst Alex Armlovich calls this pattern “missing massive” development, in contrast to the “missing middle” housing idealized by many urban planners. It’s a pattern that’s commensurate with the housing need in a region with an extreme shortage, and complimentary to a transit system like PATH. Missing massive development deserves more attention from advocates, researchers and policymakers. It ought to be evaluated on its own terms, distinct from traditional downtown high-rise development, suburban edge cities, or missing middle housing.

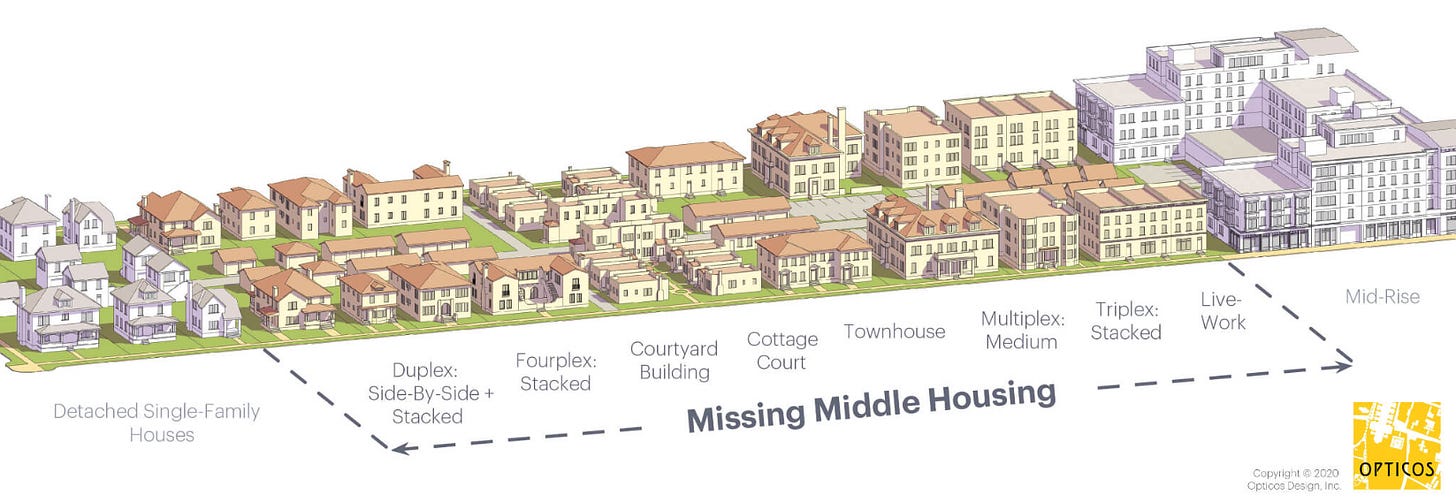

In the vast majority of residential neighborhoods in the U.S., missing middle housing — duplexes, townhomes, ADUs, cottage clusters, and small apartment buildings with fewer than ten or so units — will go a long way towards easing the affordability crunch and opening up neighborhoods to more diverse households.

Missing middle housing essentially seeks to reincarnate historic streetcar suburbs. Today, this development pattern should be the norm in neighborhoods with frequent bus service, or areas that are a mile or two from a subway, light rail, or commuter rail stop.

But what about the areas right on top of a high-capacity, high-frequency rapid transit line, like PATH, the NYC Subway, BART, and DC Metro; or a high-quality commuter rail service, like Caltrain or the LIRR? Here, urbanists should think bigger.

Big ass trains, arriving every 15 minutes or better, are symbiotic with super high-density urbanism. (Case in point: Vancouver.) These should be mixed-use neighborhoods, combining housing, commercial, and institutional structures. Missing massive doesn’t necessarily have to mean high rises, either. Washington, DC, for instance, does missing massive density within its strict height limits. Thanks to the development in NoMa and the Navy Yard, DC is one of very few coastal cities that comes close to Jersey City’s growth rate in recent years.

But DC and JC are exceptions. Outside of big city downtowns, only a handful of neighborhoods around the country reflect this transit-oriented, missing massive pattern. I explored many of them over the course of my book research:

The New York area has a few of these clusters besides Jersey City, including Long Island City, Jamaica, New Rochelle, and White Plains.

The Bay Area has Oakland’s MacArthur Commons and a handful of emerging clusters of density around Caltrain stations in Redwood City, San Mateo, Sunnyvale, and elsewhere.

In addition to the aforementioned neighborhoods in the District itself, the DMV has several edge cities like Crystal City and Tyson’s Corner, Virginia with missing massive levels of density right next to transit. Bethesda, Maryland has added some very large, very stately modern apartment houses around its Metro stop.

West LA has a couple of tower clusters rising along the Expo Line, at La Cienega and in Culver City.

Oak Park, Illinois, host to the largest concentration of Frank Lloyd Wright homes, has added a few towers near its CTA and Metra stops.

Bellevue, Washington was already a high-rise edge city, but the opening of the Line 2 light rail service last year has made it truly transit-oriented.

Many other cities have secondary high-rise districts that are not particularly transit-accessible, the classic edge city as defined by Joel Garreau. In Garreau’s telling, these are primarily commercial hubs, but over the past thirty years more primarily residential edge cities have emerged. These are among the most maddening urban environments in America, with lots of density designed exclusively around travel by car.

Uptown Dallas is one place where tower clusters exist just beyond the walking radius of the light rail system. Edgewater and Wynwood in Miami evince the same pattern. Southern California infamously has a bunch of peripheral downtowns without rapid transit access.

But in LA and across the country, there are plans underway to bring transit to edge cities, thus creating the potential for them to become truly urban missing massive neighborhoods. In other cases, plans are being made to add missing massive density to existing transit stations.

The long awaited Wilshire Boulevard subway in LA, expected to open up in segments over the next three years, will finally bring rail rapid transit to the high-rise clusters in Beverly Hills, Century City, and Westwood.

In NorCal, developers have the go ahead to build several high-rises around the West Oakland BART station, though these projects are currently stalled. Berkeley’s BART station parking lots are slated for fairly high-density development as well. San Francisco’s proposed “family zoning plan” seeks to legalize buildings over 100 hundred feet high around Balboa Park, Glen Park, Castro, and Church stations.

In Miami, Spanish developer Pablo Castro, is poised to break ground soon on a 4,000 unit workforce housing project next to the Hialeah Metrorail station, benefiting from recently passed state zoning rules and tax breaks.

In Honolulu, policymakers like state Senator Stanley Chang envision “forests of towers” on the state-owned land around the partially completed Skyline automated metro system. This is where Chang hopes to push forward the state’s mixed-income social housing program, while also combatting urban sprawl. In an interview for my book, Chang told me he’s inspired by the cities of Europe and East Asia, where high-density, mixed-income, publicly led development and high-quality transit are all part of the same city-building template.

There are more places where these kinds of projects are being contemplated, and many, many more where they ought to be. Though New York City has more missing massive developments than any other metro area, it still has an astonishing number of subway and close-in regional rail stops surrounded by single-family homes and strip malls.

There are better and worse ways to go about constructing missing massive development. Narrower buildings are almost always my preference over wide ones. They allow for piecemeal development that leaves older buildings intact, and preserves a diversity of building types and ages. But sometimes, this ideal is at odds with maximizing density. There can also be issues with integrating high-rises into low-rise blocks.

The upzoned side streets of Journal Square, in Jersey City, are surreal. There are forty story monoliths directly abutting ramshackle single-family homes. The super-high-density zoning in the area (again, with significantly higher floor-area ratios than are allowed in Manhattan) means new towers are built to the property line, with virtually no open space or setbacks. The uniformly gray color palette of the new buildings doesn’t help ingratiate them with their neighbors, either. It’s a claustrophobic and uninspired streetscape.

Missing massive development comes with major design challenges. Architects and planners will have to get creative to make these neighborhoods beautiful and livable. Though it should also be said that built-out neighborhoods like Journal Square are a harder case. The task is much easier when dealing with the blank slate of a large contiguous property, as in Europe’s finest eco-districts.

However surreal Journal Square appears today, there’s something equally surreal about a subway station surrounded by single-family homes. This is not a “normal” or “organic” pattern of urban development. It certainly doesn’t reflect the demand to live and work in these places, or the optimal land use for a quality transit system. It’s time to think seriously about what comes next.

This article has been updated to include additional development hot spots in Jersey City.

Would love to see some suggestions for how to add better streetscapes around these massive buildings. I also think I’ve seen suggestions of styling the first couple of floors to have different entrances and colors so that they feel more human scale

The photos remind me of “village in the city” in Shenzhen and Guangzhou