Trains and transmission: A climate solution hiding in plain sight?

In its final days, the Biden Administration endorsed a plan to revolutionize railroads and electricity transmission. California just released a similarly ambitious rail plan.

What if there were a way to curb climate change, expand access to clean energy, and significantly improve freight and passenger rail service all at the same time?

There just might be. It involves building long-distance transmission lines along railroad rights of way. The energy coursing through those wires could then feed overhead electric catenary to power cleaner, faster and more frequent trains. Advances in battery technology mean this vision could potentially be achieved for less money than previously imagined.

The federal government has effectively endorsed this vision with a new report from the Department of Energy, the Department of Transportation and other agencies called, “An Action Plan for Rail Energy and Emissions Innovation.”

The plan, released in December, is a parting gift from the Biden Administration to environmental and transportation advocates who have been calling for these kinds of policies for years. One of those advocates is Bill Moyer, whose 2016 book Solutionary Rail helped popularize the idea of co-locating transmission lines on railroad corridors.1

Though he acknowledges that actually building the infrastructure called for in the plan will be a difficult task during the Trump Administration, he’s not giving up hope. “There's no doubt there needs to be national leadership,” Moyer told me. “The trick for creating such leadership is to describe the project in terms that deliver benefits to the constituencies of both parties.”

The plan paints a picture of how railroad electrification can achieve a number of goals at once.

Electrification can allow for cleaner, faster, better passenger rail service, as I’ve discussed at length in this newsletter. But it can also improve freight rail operations by hauling more goods, more quickly with much less energy, potentially enabling rail to capture more of the shipping market.

“There's a strong public interest” in moving freight from trucks to trains, Moyer said. “There's a greenhouse component of the damage that those trucks are doing, but there are many other components,” he said, including wear and tear on roads, street safety, and increasing domestic manufacturing capacity.

Though it doesn’t dismiss hydrogen or battery-electric trains, the plan suggests overhead wires are the optimal way to go for a decarbonized railroad sector. It notes the extent of rail electrification around the world, even in other geographically large countries like China, India and Russia.

However, it endorses electrification with a twist. The plan is bullish on “discontinuous catenary”: stringing wires over alternating segments of a given route. Trains would be directly powered by the wires while running beneath them, and would run on batteries (or even diesel or hydrogen, if need be) the rest of the way. “Advances in battery technology are making discontinuous electrification far more feasible than we thought it would ever be if we were dependent upon acid batteries,” Moyer said.

Moyer began to take discontinuous catenary more seriously once he realized “the price of electrification in the U.S. had been exaggerated because it was including the lifting of overpasses, the crowning of tunnels and the rebuilding of bridges. But having the battery backup is a potential way to eliminate those most expensive parts of an electrification program.”

This would help to address the cost issue that has so far caused big railroad companies to dismiss electrification. They say electrifying the national rail network would cost “hundreds of billions” of dollars.

Building transmission lines on railroad corridors could help subsidize electrified rail infrastructure. The U.S., infamously, lacks a single nationwide electricity grid. It also lacks sufficient transmission capacity to move clean energy from the sunny, windy places where it is produced to the cities and factories where it is used. This problem is becoming all the more acute as more power-hungry data centers and electric vehicles come online.

A huge impediment to transmission development, and, by extension, the energy transition itself, is securing the right of way for power lines. Environmentalists, Native American tribes, and neighboring property owners, understandably, don’t want ugly metal towers and wires in pristine areas. But railroad corridors are already disturbed. Railroad companies in some cases own the land 100 feet from the tracks, leaving space for transmission lines.

This system could be mutually beneficial for railroads, utilities and the public. Railroads would get a growing freight market share on faster, more powerful electrified freight trains, and potentially, fees from energy developers. Utilities would get the long-distance transmission lines they desperately need to meet growing power demand. The public would get cleaner air and better passenger rail.

The plan gets specific about which corridors are best suited for electrification and transmission lines, based on renewable energy resources and grid needs. It’s the first time the federal government has published a map of potential electrified railroad corridors since 1983.

It likewise highlights the regional rail networks that are strong candidates for electrification, following Caltrain’s successful electrification initiative. These corridors tend to be those that are largely publicly owned and have high travel demand, including regional networks in Los Angeles, Salt Lake City, Chicago, Washington, DC, and the New York area. Short intercity routes, including the Southeast Corridor from Washington to Raleigh, the Piedmont service connecting North Carolina’s major cities, the Empire Service across New York state, and the Wolverine connecting Detroit and Chicago, are all strong candidates for electrification, according to the document.

********

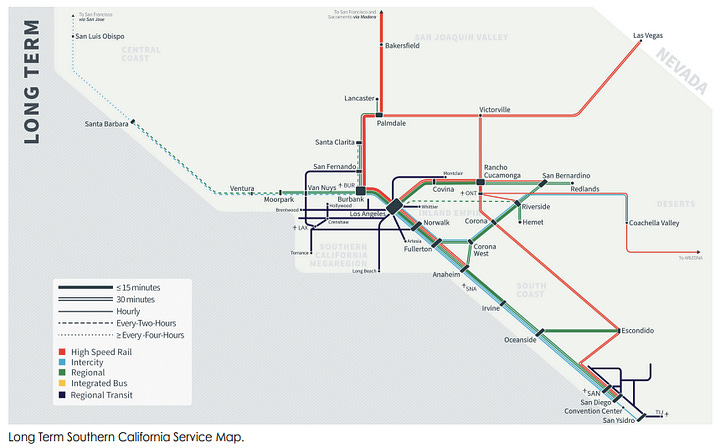

Within days of the federal government’s report, California released its long-awaited state rail plan. It, too, opts for a maximalist approach that will please advocates. The plan calls for the electrification of 1,500 miles of track by 2050, encompassing most of the state’s busiest passenger rail corridors.

Ironically, the California rail plan arrives as the state invests hundreds of millions of dollars on hydrogen trains and fueling infrastructure. This suggests the state really does view hydrogen as an interim power source that would meet climate goals in the medium term before overhead catenary can be built out, as a Caltrans’ executive told me last year. Nonetheless, now that electrification is the official long term plan, it calls into question whether the interim investment in hydrogen is worth it.

The rail plan doubles down on high-speed rail, calling for the completion of the full phase one CAHSR project connecting LA to San Francisco, and the phase two segments linking San Diego and Sacramento, along with the Brightline West project connecting Southern California and Las Vegas. It also endorses as yet un-planned high-speed rail connections to Arizona, and the extension of California High Speed Rail through a new Transbay Tube to Oakland and Richmond.

These maps published by the federal and California governments are, for the foreseeable future, just crayon drawings without money or legislation behind them.

Even using cheaper discontinuous catenary, these projects will require many billions of dollars to complete. The federal government — which is not poised to be very generous to rail in the near future — would in all likelihood need to be involved in any kind of significant electrification program.

But it matters that these documents exist in the real world, with the imprimatur of major government agencies. Now that the vision has been articulated, it’s possible to imagine pieces of this larger plan coming together if railroads and utilities begin to see it in their financial best interest.

Expanding transmission capacity is already an urgent national priority, and will only become more so as the AI race heats up. Companies like Microsoft and Alphabet are investing billions on data centers and their attendant energy needs. That’s a train railroad companies and utilities would be wise to hop on.

To learn more about the Solutionary Rail concept, check out Bill Moyer’s recent appearance on the “Volts” podcast.

You left out one fuel type: Renewable Natural Gas or RNG. You may want to learn what OptiFuel Systems of Beaufort, South Carolina has got going development-wise in the RNG-fuel space.